News / National

Reasons why South Africans treat the 13 digit ID number like a qualification

29 Oct 2024 at 14:20hrs | Views

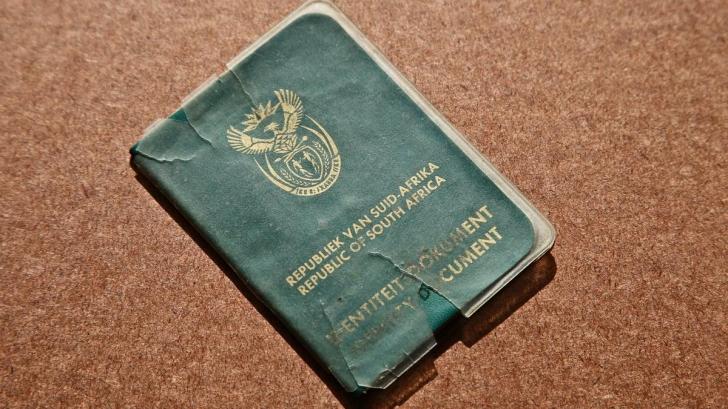

South Africa's green ID book has been used as the country's main identity document for 44 years, during which time it has only received a handful of minor security upgrades. Blacks only started using the ID after 1984 as it was only reserved for special South Africans.

The ID book has become highly susceptible to modification and forgery by fraudsters and identity thieves.

These criminals cause huge headaches for people who have their ID numbers hijacked for access to credit, loans, and other financially compromising services.

The Department of Home Affairs is in the process of replacing these books with smart ID cards.

However, its effort is several years behind schedule, and many millions of South Africans are still using the green ID book as their primary identification document.

To understand how this came to be, MyBroadband looked at the history of identification documents in South Africa.

The first formal identification document in the country was the hard plastic green ID card.

Introduced in the early 1950s, shortly after the beginning of Apartheid, the card was issued only to White, Coloured, and Indian citizens.

Due to diplomatic relations with Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, immigrants from these countries were also regarded as "honorary" whites.

The card included a photograph of the ID holder imprinted on the top left corner and an ID number of nine digits at the top right, followed by a letter for racial classification.

The ID holder's surname and initials were printed beneath the photograph, while their sex was indicated in the middle of the card.

In 1952, the much-loathed Reference Book, which would later become known as the "dompas", became mandatory for Black people from 16 years of age.

Once again, due to diplomatic relationships, "Black" people included Chinese immigrants.

All dompas holders had to carry their documents at all times as it was used to limit them to living and working within certain areas.

It also included a unique nine-digit number but had far more details about the person than the green card, including their residential details, employment and tax status, and a photograph embossed with the coat of arms.

First ID book introduced

By 1958, South Africa's interior minister reported that 95% of all coloured, Indian, and white people had received green cards.

The government initially persuaded people to take up the cards by making them a requirement for various programmes with social benefits - including teacher training, government pensions, and nursing registration.

In 1963, it also began requiring white citizens to show their ID upon police request. All citizens had to present their ID book when entering a shop, hotel, public transport, and accessing other services.

The original ID cards were issued until the 1970s and were supposed to be replaced by the controversial blue "Book of Life" ID first introduced in 1972.

The ID book was intended to be a type of "all-in-one" document and had over 50 pages for keeping track of an enormous amount of personal information, including:

- Birth certificates

- Marriage certificates

- Death certificates

- Divorces and widow status

- Naturalisation status

- Driving licences

- Medical information including blood group, vaccinations and immunisations

Initial demand for the document was so high that the government had to limit applications to voters in specific districts and to 16-year-olds who had no other forms of identification.

However, interest quickly waned, and over six years into its launch, only around half the target population of 7.5 million people had not yet received their Book of Life.

It ultimately proved impractical to bring together all of the different documents overseen by different arms of the state, with the book's pages largely left empty.

The green ID book emerges

The much smaller and simplified 16-page green ID book was introduced as an alternative in 1980 and came with 16 pages.

In addition to Whites, Coloureds, and Indians, people of Malay, Chinese, Griqwa, "other Asian" descent were allowed to apply for this ID book.

It came with a 13-digit ID number that included two digits for racial classification, a six-digit birth date, and four digits assigned according to gender and order of registration. The final digit was used as a control digit.

In addition to basic personal information that was available on the previous card, the ID book also contained marriage particulars, tax status, and firearm licences.

With the advent of South Africa's democracy in 1994, black people received full citizenship rights, including the right to the same green ID book as people of other races.

From 1 July 1996, the DHA introduced a revised ID book with just eight pages. These books use a new ID number system with racial classifications removed.

While the ID number no longer tracks a person's race, the seventh digit indicates sex, and the eleventh digit distinguishes between citizens and permanent residents.

Home Affairs also added a scannable barcode to the document and the prerequisite for cardholders to scan their fingerprints during application.

The biometric data is stored on the National Population Register, which can be referenced when scanning the ID book to lower the risk of document duplication and fraud.

The barcode helps reduce human error and makes enrollment for services faster, but it has limited security benefits.

It can even be decoded by scanners readily available on the market, which are also used by security companies for collecting data on people who enter estates, office parks, and other areas with restricted access.

The last security change for the ID book was in 2000, when Home Affairs started issuing IDs with the holder's photo digitally printed in black and white instead of being pasted or hot-laminated into the book.

That was intended to make it more difficult to create forgeries by swapping out the photo.

Lastly, the new South African coat of arms replaced the old one.

Slow smart ID card rollout

In the 24 years since these changes were introduced, technology has advanced rapidly and made it far easier to duplicate, modify, or forge ID books.

In addition, green ID books issued as far back as 1980 remain valid, weakening the impact of the improvements.

While much has recently been made about the green ID book's outdated security features and susceptibility to identity theft, this has been a "major concern" for the government for over a decade.

When the smart ID card was announced in 2013, GCIS CEO Phumla Williams described it as a "quantum leap" from its predecessor, which was "old", "antiquated", and "open to fraud."

"The smart card will cut down on the fraudulent use of fake or stolen IDs, which is a major concern," Williams said.

"It uses sophisticated and secure technology systems to manage identity in South Africa."

The card includes a chip storing the holder's data, which is laser-engraved to prevent tampering.

Despite government's keen awareness about the severe security issues with the green ID book, it has only rolled out systems required to issue smart ID cards to two thirds of its offices.

While it had initially planned to have fully replaced the now 44 year-old green ID books by 2021, it has only issued 26 million Smart ID cards against an original target of 38 million books in the past 11 years.

The ID book has become highly susceptible to modification and forgery by fraudsters and identity thieves.

These criminals cause huge headaches for people who have their ID numbers hijacked for access to credit, loans, and other financially compromising services.

The Department of Home Affairs is in the process of replacing these books with smart ID cards.

However, its effort is several years behind schedule, and many millions of South Africans are still using the green ID book as their primary identification document.

To understand how this came to be, MyBroadband looked at the history of identification documents in South Africa.

The first formal identification document in the country was the hard plastic green ID card.

Introduced in the early 1950s, shortly after the beginning of Apartheid, the card was issued only to White, Coloured, and Indian citizens.

Due to diplomatic relations with Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, immigrants from these countries were also regarded as "honorary" whites.

The card included a photograph of the ID holder imprinted on the top left corner and an ID number of nine digits at the top right, followed by a letter for racial classification.

The ID holder's surname and initials were printed beneath the photograph, while their sex was indicated in the middle of the card.

In 1952, the much-loathed Reference Book, which would later become known as the "dompas", became mandatory for Black people from 16 years of age.

Once again, due to diplomatic relationships, "Black" people included Chinese immigrants.

All dompas holders had to carry their documents at all times as it was used to limit them to living and working within certain areas.

It also included a unique nine-digit number but had far more details about the person than the green card, including their residential details, employment and tax status, and a photograph embossed with the coat of arms.

First ID book introduced

By 1958, South Africa's interior minister reported that 95% of all coloured, Indian, and white people had received green cards.

The government initially persuaded people to take up the cards by making them a requirement for various programmes with social benefits - including teacher training, government pensions, and nursing registration.

In 1963, it also began requiring white citizens to show their ID upon police request. All citizens had to present their ID book when entering a shop, hotel, public transport, and accessing other services.

The original ID cards were issued until the 1970s and were supposed to be replaced by the controversial blue "Book of Life" ID first introduced in 1972.

The ID book was intended to be a type of "all-in-one" document and had over 50 pages for keeping track of an enormous amount of personal information, including:

- Birth certificates

- Marriage certificates

- Death certificates

- Divorces and widow status

- Naturalisation status

- Driving licences

- Medical information including blood group, vaccinations and immunisations

Initial demand for the document was so high that the government had to limit applications to voters in specific districts and to 16-year-olds who had no other forms of identification.

However, interest quickly waned, and over six years into its launch, only around half the target population of 7.5 million people had not yet received their Book of Life.

It ultimately proved impractical to bring together all of the different documents overseen by different arms of the state, with the book's pages largely left empty.

The green ID book emerges

In addition to Whites, Coloureds, and Indians, people of Malay, Chinese, Griqwa, "other Asian" descent were allowed to apply for this ID book.

It came with a 13-digit ID number that included two digits for racial classification, a six-digit birth date, and four digits assigned according to gender and order of registration. The final digit was used as a control digit.

In addition to basic personal information that was available on the previous card, the ID book also contained marriage particulars, tax status, and firearm licences.

With the advent of South Africa's democracy in 1994, black people received full citizenship rights, including the right to the same green ID book as people of other races.

From 1 July 1996, the DHA introduced a revised ID book with just eight pages. These books use a new ID number system with racial classifications removed.

While the ID number no longer tracks a person's race, the seventh digit indicates sex, and the eleventh digit distinguishes between citizens and permanent residents.

Home Affairs also added a scannable barcode to the document and the prerequisite for cardholders to scan their fingerprints during application.

The biometric data is stored on the National Population Register, which can be referenced when scanning the ID book to lower the risk of document duplication and fraud.

The barcode helps reduce human error and makes enrollment for services faster, but it has limited security benefits.

It can even be decoded by scanners readily available on the market, which are also used by security companies for collecting data on people who enter estates, office parks, and other areas with restricted access.

The last security change for the ID book was in 2000, when Home Affairs started issuing IDs with the holder's photo digitally printed in black and white instead of being pasted or hot-laminated into the book.

That was intended to make it more difficult to create forgeries by swapping out the photo.

Lastly, the new South African coat of arms replaced the old one.

Slow smart ID card rollout

In the 24 years since these changes were introduced, technology has advanced rapidly and made it far easier to duplicate, modify, or forge ID books.

In addition, green ID books issued as far back as 1980 remain valid, weakening the impact of the improvements.

While much has recently been made about the green ID book's outdated security features and susceptibility to identity theft, this has been a "major concern" for the government for over a decade.

When the smart ID card was announced in 2013, GCIS CEO Phumla Williams described it as a "quantum leap" from its predecessor, which was "old", "antiquated", and "open to fraud."

"The smart card will cut down on the fraudulent use of fake or stolen IDs, which is a major concern," Williams said.

"It uses sophisticated and secure technology systems to manage identity in South Africa."

The card includes a chip storing the holder's data, which is laser-engraved to prevent tampering.

Despite government's keen awareness about the severe security issues with the green ID book, it has only rolled out systems required to issue smart ID cards to two thirds of its offices.

While it had initially planned to have fully replaced the now 44 year-old green ID books by 2021, it has only issued 26 million Smart ID cards against an original target of 38 million books in the past 11 years.

Source - mybroadband