News / National

Eswatini want its land from South Africa

21 May 2025 at 20:07hrs | Views

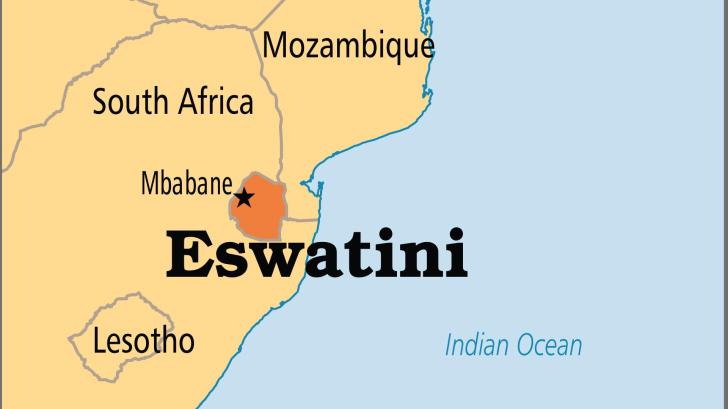

The King of Eswatini, Mswati III, has revived his kingdom's longstanding territorial claims against South Africa by appointing a new Border Restoration Committee (BRC), tasked with negotiating the return of land stolen during the colonial era.

The newly announced 15-member committee, which includes several royal family members and loyal monarchists, was unveiled on Monday. It will serve a five-year term and is the latest in a series of similar committees formed by the kingdom over the past decades. Despite repeated appointments, no progress has been made in reclaiming the disputed land.

Chief Mgebiseni Dlamini, a distant relative of King Mswati III, has been named chairperson of the committee. Speaking during the announcement, the King said the committee's mandate is to engage with South African authorities to push for the return of territories Eswatini claims were unjustly taken during the colonial period, particularly by Afrikaner farmers who initially leased the land before allegedly securing ownership through skewed arrangements.

The Eswatini monarchy maintains that vast areas of present-day South Africa, especially Mpumalanga province - formerly known as the Eastern Transvaal - were historically part of the Swazi kingdom. The current borders, they claim, were not only a product of colonial conquest but were also further distorted in the 1970s and 1980s by South African authorities using disease control, particularly foot and mouth outbreaks, as a pretext to redraw boundaries.

The kingdom is also asserting claims over portions of Gauteng province, including the town of Springs near Johannesburg, as well as several towns in KwaZulu-Natal. Eswatini argues that the Pongola River was historically the natural boundary between the Swazi and Zulu kingdoms, meaning towns such as Pongola, Ingwavuma, and Kosi Bay lie within Eswatini's rightful territory. The kingdom also emphasizes the spiritual significance of the Indian Ocean coast, where it traditionally collected sea water for sacred rituals like Incwala.

In 1982, the apartheid government of South Africa entered into an agreement with Eswatini to cede portions of Ingwavuma. However, the deal was blocked in court after legal action by the late Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi, then the leader of the KwaZulu homeland government. The agreement was nullified, and the land remained under South African jurisdiction. In a show of control over the area, the KwaZulu government later built the Machobeni Royal Palace and held Zulu cultural events on the contested land.

Despite the symbolism of the BRC's reformation, critics have expressed skepticism about its effectiveness. Similar committees have been established every five years with little tangible progress in resolving the land dispute. Nonetheless, the Eswatini monarchy remains committed to pursuing its claims and views the matter as part of a broader struggle to reverse colonial-era injustices.

There has been no official response from the South African government regarding the new BRC or Eswatini's latest push to revisit territorial boundaries. The situation adds to ongoing discussions in the region about colonial borders and the lingering legacy of imperial land arrangements in post-independence Africa.

The newly announced 15-member committee, which includes several royal family members and loyal monarchists, was unveiled on Monday. It will serve a five-year term and is the latest in a series of similar committees formed by the kingdom over the past decades. Despite repeated appointments, no progress has been made in reclaiming the disputed land.

Chief Mgebiseni Dlamini, a distant relative of King Mswati III, has been named chairperson of the committee. Speaking during the announcement, the King said the committee's mandate is to engage with South African authorities to push for the return of territories Eswatini claims were unjustly taken during the colonial period, particularly by Afrikaner farmers who initially leased the land before allegedly securing ownership through skewed arrangements.

The Eswatini monarchy maintains that vast areas of present-day South Africa, especially Mpumalanga province - formerly known as the Eastern Transvaal - were historically part of the Swazi kingdom. The current borders, they claim, were not only a product of colonial conquest but were also further distorted in the 1970s and 1980s by South African authorities using disease control, particularly foot and mouth outbreaks, as a pretext to redraw boundaries.

The kingdom is also asserting claims over portions of Gauteng province, including the town of Springs near Johannesburg, as well as several towns in KwaZulu-Natal. Eswatini argues that the Pongola River was historically the natural boundary between the Swazi and Zulu kingdoms, meaning towns such as Pongola, Ingwavuma, and Kosi Bay lie within Eswatini's rightful territory. The kingdom also emphasizes the spiritual significance of the Indian Ocean coast, where it traditionally collected sea water for sacred rituals like Incwala.

In 1982, the apartheid government of South Africa entered into an agreement with Eswatini to cede portions of Ingwavuma. However, the deal was blocked in court after legal action by the late Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi, then the leader of the KwaZulu homeland government. The agreement was nullified, and the land remained under South African jurisdiction. In a show of control over the area, the KwaZulu government later built the Machobeni Royal Palace and held Zulu cultural events on the contested land.

Despite the symbolism of the BRC's reformation, critics have expressed skepticism about its effectiveness. Similar committees have been established every five years with little tangible progress in resolving the land dispute. Nonetheless, the Eswatini monarchy remains committed to pursuing its claims and views the matter as part of a broader struggle to reverse colonial-era injustices.

There has been no official response from the South African government regarding the new BRC or Eswatini's latest push to revisit territorial boundaries. The situation adds to ongoing discussions in the region about colonial borders and the lingering legacy of imperial land arrangements in post-independence Africa.

Source - African Times