Opinion / Interviews

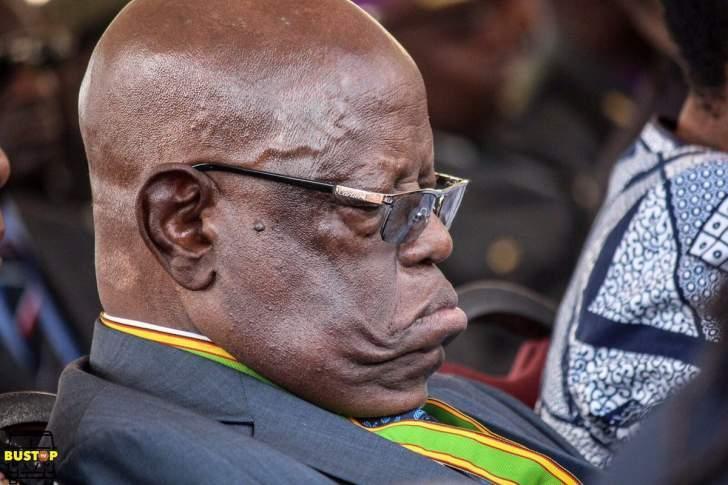

Pioneer guerilla Tshinga Dube speaks on first operations

28 Apr 2019 at 06:45hrs |

4488 Views

IN our past two editions we published the military and political exploits of renowned pioneer guerilla fighter, David Mongwa Moyo aka Sharpshoot.

Moyo spoke about his deployment in a unit of 10 guerillas that laid the foundation for the historical Wankie (Hwange) battles in 1967, which was a joint operation between Zapu and ANC guerillas, the Umkhonto WeSizwe (MK). Among those in that unit of 10 guerillas was now Retired Colonel Tshinga Judge Dube, who was later on to become Zipra's Chief of Communications.

Rtd Col Dube is also a former chief executive officer of the Zimbabwe Defence Industries (ZDI), board member of some parastatals, Member of Parliament for Makokoba and a Cabinet Minister.

Our Assistant Editor Mkhululi Sibanda on Thursday spoke to Rtd Col Dube to get an insight into the first military operations during the armed struggle.

MS: Many know Rtd Col Tshinga Dube as you are a public figure, but may you please tell us where you were born and bred. Just your brief background.

Rtd Col Dube: I was born on 3 July in 1941 at Fort Usher, eFodini in Matobo District, Matabeleland South Province. I did my primary education for the first two years at the local school at my rural home in Matobo. I then moved to Mzilikazi Primary School here in Bulawayo and later on to Solusi Mission for my secondary education. However, I had wanted to do my secondary education at Goromonzi, but because my father, Judge Dube was a pastor at the Seventh Day Adventist Church, he insisted that I go to Solusi, which is an SDA school. As for my parents, they were both teachers, my father, Judge and my mother, Jane. My father later on went to head various schools.

MS: Then there is politics, what influenced you to join politics?

Rtd Col Dube: During our time at Solusi, teachers, especially one called Kopolo used to tell us about Ghana, which was enjoying self rule after getting its independence from Britain in 1957. That was an inspirational story to us as youngsters and so that feeling of having our own country become independent inspired us. So when I completed my secondary school I had that drive of leaving the country and going to Ghana. We also used to read about Kwame Nkrumah, the man who had led Ghana to independence. So after 1961 I left the country for Zambia with the intention of proceeding to Ghana. I wanted to live in a free country. Then it happened that while in Zambia I joined the structures of Zapu and later on became secretary for Luwanshe District. I got a job in Zambia at a company called Sables, the job was a lucrative one. I rose to become deputy manager at that company, which was the first to sell items like radios, watches, motor cycles and things like that on hire purchase to the blacks.

MS: With such a promising life you still decided to leave that job for politics and join the armed struggle?

Rtd Col Dube: My life was beginning to shape up in the right direction and I had managed to get a house where I was being visited by people from home. I remember I used to host guys like Edward Bhebhe, Dumiso Dabengwa, Amos Jack Ngwenya among a host of others. I was now deep into politics. Then I was told that I had been selected to go for military training in the Soviet Union. I left my job with all its good trappings to embark on a journey to free my country and I never regretted that decision.

MS: Which year was that when you were chosen to go for military training?

Rtd Col Dube: That was in 1964 in June. We were a group of 12 and ours is the one that came after that of Dumiso Dabengwa, Report Mphoko, Robson Manyika, Goche not Nicholas the former Cabinet Minister, there was another Goche. That group of Dabengwa and Mphoko went to the Soviet Union in April 1964 and ours followed about two months later.

MS: Who was in your group?

Rtd Col Dube: Among the 12 were Roger Ncube (Matshimini), John Ntemba, Moffat Ndlovu, the former Bulawayo Town Clerk, Peter Madlela, Zephania Ngungu, Tichafa and others. We were very excited when we started our military training, that feeling of holding and using a gun excited us a lot. We thought we had already got the country. At that time during training we thought it would be easy for us to march all the way to Salisbury (Harare). We didn't know what was ahead of us. After going through all the rudimentary of military training we were tasked to specialise in some aspects and I was chosen to do military communications. At the end of our training I remained there as I was selected to be a part-time instructor to the group that came after us. The Soviet instructors felt I had been a brilliant recruit and so I could be helpful. Then at the end of 1965 I returned to Zambia and stayed at the camps. During that time we were very few, I mean the trained personnel. However, a command structure was in place, which had Dabengwa and Ethan Dube in the security department, Robson Manyika as chief of staff and so on. I later lived at Nkomo Camp, which was under the command of Mphoko. I stayed there for a few months before I was deployed to the front.

MS: Take us through your deployment.

Rtd Col Dube: I was in a unit of 10 guerillas and during that time the armed struggle was at its infancy. We did not have things like dinghies to cross the mighty Zambezi River infested with crocodiles and hippos, which was a very big obstacle to the guerillas. So we used canoes with the assistance of the Barotse people. They were very helpful. The canoes were a challenge themselves as during the course of crossing water would fill in and we had to use our hands to scoop it out. There was also the anxiety that maybe the enemy forces were waiting on the other side. It was arranged that we would be met by a white man called Peter Mackay who supported our struggle for independence. He is the one who drove us through Botswana when we were on the other side. He left us on the side that was closer to Tsholotsho District. Yikho esangenela khona eTsholotsho.

MS: In that unit of 10 who were the other guerillas?

Rtd Col Dube: Our unit was under the command of Matshimini while myself I was the communications man as well as political commissar. Also in that unit were comrades like David Mongwa Moyo, uSharpshoot and John Ntemba. Our weaponry was very poor as we were armed with Pepeshas and Siminov. However, we also had a bazooka, pistols and grenades.

MS: How was the situation like considering that the masses were not used to seeing guerillas?

Rtd Col Dube: It was tricky, but we were helped by the fact that John Ntemba's father was a herbalist and popular man in that area of Tsholotsho, so we had somewhere to start from in organising the people. Our unit's objective was to mobilise the masses, recruit and lay the ground for units that were to come later. At first we were avoided in engaging in open combat with the enemy forces, considering our numbers and types of weapons that we were armed with. We based at Cawunajena, a remote part of Tsholotsho. We made friends with the San community and lived among them. You know the San love smoking imbanje and I remember we brought them some, there were 25 of them and they were so happy. They liked us a lot and we felt a little bit safe among them.

MS: That is interesting.

Rtd Col Dube: When we had won their trust, the San people are into rituals and I remember one of their community leaders told us that he wanted to perform some rituals on us and we agreed. He smeared some concoctions on our foreheads and other parts of the body, which he said would keep us away from danger. I should confess those things work and in the situation we were in it worked. You know you would dream things that would happen exactly the way you had seen them in your sleep. People might even think you are communicating with the whites. You know the San are gifted a lot, they have their own science, which is amazing.

MS: Was your unit still intact?

Rtd Col Dube: We had split into smaller groups, now we had three groups, Sharpshoot had taken two other comrades with him to Kezi while mine had four guerillas including myself and the third had three comrades. We could not move in the original number of 10 as we feared being easily detected. My unit is the one that based in Tsholotsho while others moved to others areas, but they were supposed to come back to Tsholotsho as it was the main base.

MS: You spoke about recruitment, how were people responding?

Rtd Col Dube: It went well especially as there were people who were coming from detention at places like Gonakudzingwa, they were eager to go and join the armed struggle. But in the 60s very few people were convinced that the white settler regime could be defeated. We worked under those difficult circumstances and we preserved. The settler regime had a policy of paying villagers who would report the presence of guerillas to the authorities, people were paid $10, which was an attractive amount during those days. So there was also the issue of sell-outs to contend with.

MS: How did you deal with sell-outs?

Rtd Col Dube: It was a delicate situation, there was one man called Ngulube there in Tsholotsho who was in the habit of informing the authorities about the nationalists' political activities. So to stop him from selling out we agreed not to kill him. So we came up with a plan of setting him against his masters. We raided his home at night and asked him to accompany us. We told him that we wanted to address the villagers during that night and he should go with us. We moved from homestead to homestead waking up the people and he is the one who was doing that while we remained in the background. We would move with him to a homestead and ask him to go and wake up the people. He did that and we covered about 30 homesteads. The people were shocked to see him doing that. The meeting was held and there in front of the people we thanked him for a job well done in organising the meeting. From that day whenever he heard the sound of a vehicle he would flee to the bush in fear of being arrested because he thought other villagers had sold him out. He stopped his nefarious activities of selling out. At times there was no need to use brawn to deal with such people, but brains.

To be continued next week

Moyo spoke about his deployment in a unit of 10 guerillas that laid the foundation for the historical Wankie (Hwange) battles in 1967, which was a joint operation between Zapu and ANC guerillas, the Umkhonto WeSizwe (MK). Among those in that unit of 10 guerillas was now Retired Colonel Tshinga Judge Dube, who was later on to become Zipra's Chief of Communications.

Rtd Col Dube is also a former chief executive officer of the Zimbabwe Defence Industries (ZDI), board member of some parastatals, Member of Parliament for Makokoba and a Cabinet Minister.

Our Assistant Editor Mkhululi Sibanda on Thursday spoke to Rtd Col Dube to get an insight into the first military operations during the armed struggle.

MS: Many know Rtd Col Tshinga Dube as you are a public figure, but may you please tell us where you were born and bred. Just your brief background.

Rtd Col Dube: I was born on 3 July in 1941 at Fort Usher, eFodini in Matobo District, Matabeleland South Province. I did my primary education for the first two years at the local school at my rural home in Matobo. I then moved to Mzilikazi Primary School here in Bulawayo and later on to Solusi Mission for my secondary education. However, I had wanted to do my secondary education at Goromonzi, but because my father, Judge Dube was a pastor at the Seventh Day Adventist Church, he insisted that I go to Solusi, which is an SDA school. As for my parents, they were both teachers, my father, Judge and my mother, Jane. My father later on went to head various schools.

MS: Then there is politics, what influenced you to join politics?

Rtd Col Dube: During our time at Solusi, teachers, especially one called Kopolo used to tell us about Ghana, which was enjoying self rule after getting its independence from Britain in 1957. That was an inspirational story to us as youngsters and so that feeling of having our own country become independent inspired us. So when I completed my secondary school I had that drive of leaving the country and going to Ghana. We also used to read about Kwame Nkrumah, the man who had led Ghana to independence. So after 1961 I left the country for Zambia with the intention of proceeding to Ghana. I wanted to live in a free country. Then it happened that while in Zambia I joined the structures of Zapu and later on became secretary for Luwanshe District. I got a job in Zambia at a company called Sables, the job was a lucrative one. I rose to become deputy manager at that company, which was the first to sell items like radios, watches, motor cycles and things like that on hire purchase to the blacks.

MS: With such a promising life you still decided to leave that job for politics and join the armed struggle?

Rtd Col Dube: My life was beginning to shape up in the right direction and I had managed to get a house where I was being visited by people from home. I remember I used to host guys like Edward Bhebhe, Dumiso Dabengwa, Amos Jack Ngwenya among a host of others. I was now deep into politics. Then I was told that I had been selected to go for military training in the Soviet Union. I left my job with all its good trappings to embark on a journey to free my country and I never regretted that decision.

MS: Which year was that when you were chosen to go for military training?

Rtd Col Dube: That was in 1964 in June. We were a group of 12 and ours is the one that came after that of Dumiso Dabengwa, Report Mphoko, Robson Manyika, Goche not Nicholas the former Cabinet Minister, there was another Goche. That group of Dabengwa and Mphoko went to the Soviet Union in April 1964 and ours followed about two months later.

MS: Who was in your group?

Rtd Col Dube: Among the 12 were Roger Ncube (Matshimini), John Ntemba, Moffat Ndlovu, the former Bulawayo Town Clerk, Peter Madlela, Zephania Ngungu, Tichafa and others. We were very excited when we started our military training, that feeling of holding and using a gun excited us a lot. We thought we had already got the country. At that time during training we thought it would be easy for us to march all the way to Salisbury (Harare). We didn't know what was ahead of us. After going through all the rudimentary of military training we were tasked to specialise in some aspects and I was chosen to do military communications. At the end of our training I remained there as I was selected to be a part-time instructor to the group that came after us. The Soviet instructors felt I had been a brilliant recruit and so I could be helpful. Then at the end of 1965 I returned to Zambia and stayed at the camps. During that time we were very few, I mean the trained personnel. However, a command structure was in place, which had Dabengwa and Ethan Dube in the security department, Robson Manyika as chief of staff and so on. I later lived at Nkomo Camp, which was under the command of Mphoko. I stayed there for a few months before I was deployed to the front.

Rtd Col Dube: I was in a unit of 10 guerillas and during that time the armed struggle was at its infancy. We did not have things like dinghies to cross the mighty Zambezi River infested with crocodiles and hippos, which was a very big obstacle to the guerillas. So we used canoes with the assistance of the Barotse people. They were very helpful. The canoes were a challenge themselves as during the course of crossing water would fill in and we had to use our hands to scoop it out. There was also the anxiety that maybe the enemy forces were waiting on the other side. It was arranged that we would be met by a white man called Peter Mackay who supported our struggle for independence. He is the one who drove us through Botswana when we were on the other side. He left us on the side that was closer to Tsholotsho District. Yikho esangenela khona eTsholotsho.

MS: In that unit of 10 who were the other guerillas?

Rtd Col Dube: Our unit was under the command of Matshimini while myself I was the communications man as well as political commissar. Also in that unit were comrades like David Mongwa Moyo, uSharpshoot and John Ntemba. Our weaponry was very poor as we were armed with Pepeshas and Siminov. However, we also had a bazooka, pistols and grenades.

MS: How was the situation like considering that the masses were not used to seeing guerillas?

Rtd Col Dube: It was tricky, but we were helped by the fact that John Ntemba's father was a herbalist and popular man in that area of Tsholotsho, so we had somewhere to start from in organising the people. Our unit's objective was to mobilise the masses, recruit and lay the ground for units that were to come later. At first we were avoided in engaging in open combat with the enemy forces, considering our numbers and types of weapons that we were armed with. We based at Cawunajena, a remote part of Tsholotsho. We made friends with the San community and lived among them. You know the San love smoking imbanje and I remember we brought them some, there were 25 of them and they were so happy. They liked us a lot and we felt a little bit safe among them.

MS: That is interesting.

Rtd Col Dube: When we had won their trust, the San people are into rituals and I remember one of their community leaders told us that he wanted to perform some rituals on us and we agreed. He smeared some concoctions on our foreheads and other parts of the body, which he said would keep us away from danger. I should confess those things work and in the situation we were in it worked. You know you would dream things that would happen exactly the way you had seen them in your sleep. People might even think you are communicating with the whites. You know the San are gifted a lot, they have their own science, which is amazing.

MS: Was your unit still intact?

Rtd Col Dube: We had split into smaller groups, now we had three groups, Sharpshoot had taken two other comrades with him to Kezi while mine had four guerillas including myself and the third had three comrades. We could not move in the original number of 10 as we feared being easily detected. My unit is the one that based in Tsholotsho while others moved to others areas, but they were supposed to come back to Tsholotsho as it was the main base.

MS: You spoke about recruitment, how were people responding?

Rtd Col Dube: It went well especially as there were people who were coming from detention at places like Gonakudzingwa, they were eager to go and join the armed struggle. But in the 60s very few people were convinced that the white settler regime could be defeated. We worked under those difficult circumstances and we preserved. The settler regime had a policy of paying villagers who would report the presence of guerillas to the authorities, people were paid $10, which was an attractive amount during those days. So there was also the issue of sell-outs to contend with.

MS: How did you deal with sell-outs?

Rtd Col Dube: It was a delicate situation, there was one man called Ngulube there in Tsholotsho who was in the habit of informing the authorities about the nationalists' political activities. So to stop him from selling out we agreed not to kill him. So we came up with a plan of setting him against his masters. We raided his home at night and asked him to accompany us. We told him that we wanted to address the villagers during that night and he should go with us. We moved from homestead to homestead waking up the people and he is the one who was doing that while we remained in the background. We would move with him to a homestead and ask him to go and wake up the people. He did that and we covered about 30 homesteads. The people were shocked to see him doing that. The meeting was held and there in front of the people we thanked him for a job well done in organising the meeting. From that day whenever he heard the sound of a vehicle he would flee to the bush in fear of being arrested because he thought other villagers had sold him out. He stopped his nefarious activities of selling out. At times there was no need to use brawn to deal with such people, but brains.

To be continued next week

Source - sundaynews

All articles and letters published on Bulawayo24 have been independently written by members of Bulawayo24's community. The views of users published on Bulawayo24 are therefore their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Bulawayo24. Bulawayo24 editors also reserve the right to edit or delete any and all comments received.

Join the discussion

Loading comments…