Opinion / Columnist

Why Section 95(2)(b) is not a term-limit provision requiring a referendum

10 Dec 2025 at 07:30hrs |

0 Views

Imagine a constitution, not as an unyielding monolith cast in stone for eternity, but as a living, breathing instrument of a democratic society - crafted by the hands of our compatriots, many still among us, to evolve with national aspirations for prosperity while safeguarding against the whims of power. The Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013) embodies precisely that kid of an enlightened vision, with section 95(2)(b) elegantly prescribing a five-year cycle for the enduring institution of the presidency. This provision, attuned to unforeseen events and legal contingencies, ensures uninterrupted governance and periodic democratic renewal. It stands unequivocally as a "duration" or "term-length" clause, imposing no absolute ceiling on an occupant's cumulative tenure - a pivotal distinction that shatters the misguided belief that amending section 95(2)(b) somehow necessitates a national referendum under section 328(7). Instead, the section paves the way for thoughtful and meaningful constitutional evolution, fortifying democracy against stagnation and authoritarian backsliding.

Dispelling Dangerous Myths

Yet, pernicious myths endure, clouding this clarity and imperilling essential reforms by distorting meaningful public discourse. Detractors mistakenly describe section 95(2)(b) as a sacrosanct "term-limit provision," adamantly claiming that its amendment is unattainable - or outright forbidden for sitting incumbents - without a referendum.

This fallacy of "unconstitutionality and illegality" is touted as an incontrovertible truth, with those who assert the myth brazenly declaring - devoid of any constitutional references, logical underpinnings, or judicial precedent - that such amendments are "unconstitutional and illegal" (as echoed by public intellectuals like Sipho Malunga: (https://x.com/SiphoMalunga/status/1991739985704390825?s=20). Regrettably, some prominent voices cloak their lack of evidence in abrasive, ad hominem tactics (for instance, Thabani Mpofu, who mobilises his ilk to vilify, caricature, and demonise proponents of amendment to section 95(2)(b) while sidestepping unavoidable courtroom challenges or meaningful public debate: https://x.com/adv_fulcrum/status/1982701171937521844?s=20); or through blatant misrepresentations in lieu of evidence-driven journalism (such as NewsHawks, whose editors have blatantly and falsely alleged this writer has argued that "there is a legal lacuna, a gap or loophole in the law' which can be used to ‘unconstitutionally and illegally" amend section 95(2)(b) - https://x.com/NewsHawksLive/status/1993890303728607247?s=20. This writer has not said anywhere or anytime that there's a lacuna in the law. Quite the contrary, this writer has been emphatically clear that sections 95(2(b) and 143(1) of the Constitution are not term limit provisions and that their amendment can be constitutionally and legally done under section 328(5) without requiring a national referendum.

Such personal attacks, distortions, and inventions are not only regrettable but utterly futile, serving only to muddy the waters of reasoned public discourse.

At its core, the constitutionality or legality of any amendment to the Constitution rests exclusively on adherence to the stipulated procedures - nothing else. From the inception of the presidential term of office extension proposal, the envisioned amendment to section 95(2)(b) complies fully with section 328, as interpreted alongside section 131; no deviations have been suggested or enacted by any party.

Compounding these myths is the pervasive "myth of authority," a common pitfall in constitutional debate where revered institutions (and certain influential individuals) leverage their presumed prestige to prop up baseless claims. This approach imparts an illusion of credibility to assertions bereft of objective proof, rigorous analysis, or precedential support. A poignant and dispiriting illustration comes from VeritasZim, widely esteemed as a supposedly neutral authority on Zimbabwean jurisprudence and legal matters. On 1 March 2024, VeritasZim published a thoughtful, balanced piece entitled "Extending the Presidential Term-Limit – Can it be Done?" (available at https://www.veritaszim.net/node/6888

). Therein, they posed a fundamental query: Which constitutional clauses would require amendment to extend the presidential term? Their unequivocal answer: "The first and most obvious amendment would be to section 91, which as we have seen sets out the current presidential term-limit."

Notably - and appropriately - VeritasZim omitted any reference to additional term-limit provisions beyond section 91(2). This exclusion was logical, as no properly-drafted democratic constitution redundantly replicates term-limit stipulations; such repetition would undermine the principles of precision and economy in legal drafting. However, fast-forward a year and a half to 9 November 2025, and VeritasZim released a remarkably parallel analysis, "Can the Presidential Term-Limit Be Extended?" (found at https://veritaszim.net/node/7732

). In a dramatic about-face, they declared that "sections 91(2) and 95(2) are both term-limit provisions," citing section 328(1)'s definition of a term-limit clause as "a provision of this Constitution which limits the length of time that a person may hold or occupy a public office."

This pronouncement wields the gravitas of expertise, yet it wilts under elementary examination - a bald assertion stripped of corroborating case law, intellectual insight, or even rudimentary interpretive logic. What prompted this sudden shift? In their 2024 analysis, section 95(2) was notably absent from term-limit deliberations, rendering this a tardy addendum. The timing itself invites scrutiny, hinting at extraneous political correctness beyond professional purity.

Exacerbating the inconsistency, VeritasZim's 2025 piece opens with a solid insight: "If it is decided to lengthen the presidential term from five to seven years, then section 95(1) of the Constitution would have to be amended, because it provides that the length of the President's term of office is: 'five years and coterminous with the life of Parliament.' The words 'five years' would need to be changed to 'seven years' and the words 'coterminous with the life of Parliament' would have to be deleted unless the life of Parliament is also to be extended to seven years."

This observation aptly positions section 95 as delineating the span of a solitary presidential term - five years, synchronised with Parliament's duration - as indicated by its explicit heading. It enforces no restriction on the quantity of terms, nor does it constrain the aggregate tenure of an officeholder. How, then, does it suddenly transmute into a term-limit provision? Solely through unsupported decree, mirroring the manoeuvres of political adversaries with whom VeritasZim now seems inadvertently or deliberately aligned at this pivotal moment, absent any substantive legal grounding.

A dispassionate juxtaposition of VeritasZim's March 2024 and November 2025 analyses yields an inescapable verdict: Section 95(2) does not constitute a term-limit provision per section 328(1), lacking any overt curb on presidential tenure. Claims otherwise stem not from fidelity to the constitutional text but from partisan mythologizing. In an age that demands unyielding legal probity, these last-minute somersaults undermine credibility and highlight the perils of unexamined authority. Zimbabweans merit better public discourse - meticulous information sharing over rhetorical legerdemain.

Institutional Nature of 'Office of President'

Within Zimbabwe's Constitution, section 95(2)(b) institutes a standardized, singular-duration structure of the presidency as a perpetual public institution, guaranteeing administrative seamlessness and electoral regularity every five years, rather than enforcing a tenure cap on specific occupants of the office. This qualifies it as a "duration or term-length provision," starkly differentiated from a "term-limit provision" that imposes a cumulative cap.

As a singular-duration clause, section 95(2)(b) mandates a consistent five-year rhythm for each electoral cycle, operating as a foundational descriptor of institutional process. It refrains from overseeing the aggregated service of individual occupants across successive terms, a matter handled distinctly (notably in section 91(2), which limits to two terms, with amendments invoking section 328(7)'s referendum safeguard).

Bearing the heading "Term of office of President and Vice-Presidents," section 95 specifies that the President's term endures until a successor's inauguration following an election, rooted in a five-year foundation (section 95(1)). It operationally binds the presidency's span to electoral results, enabling fluid transitions and alignment with parliamentary cycles under section 143. Functioning as a single-term directive, it facilitates the stewardship of public office through mandated recurrent elections, without impinging on personal re-election qualifications (regulated independently by section 91(2)).

The Electoral Act [Chapter 2:13], as amended, bolsters this institutional perspective in Part XVII, headed "Provisions Relating to Elections to the Office of President." Pertinent sections uniformly invoke "office of President" in headings and substance:

Section 104: "Nomination of candidates for election to office of President," outlining prerequisites for accessing the office.

Section 109: "Procedure after nomination day in election to office of President," detailing subsequent processes, including uncontested election declarations.

Section 110: "Election to office of President," regulating polling, tabulation, runoffs, and declarations, with the winner assuming office upon oath.

Section 111: "Election petitions in respect of election to office of President," enabling Constitutional Court contests to uphold the office's sanctity.

This consistent lexicon - stressing elections "to office of President," nominations for "office of President," and petitions concerning "office of President" - compels the inference that both the Constitution and Electoral Act envision the presidency as a "public office": a lasting public entity, separable from its temporary incumbent, promoting democratic perpetuity and oversight beyond mere personal incumbency.

Building on this institutional bedrock, the Constitution intentionally deploys "his or her tenure of office" in section 97(1)(e) - activating removal if the President acquires non-honorary foreign citizenship during that interval - to delineate "tenure" as the individualised, fluctuating extent of an incumbent's actual occupancy, distinct from the institutional, invariant "term of office of President."

Section 95(2) conceptualises "term of office" as a temporal yardstick: five years, concurrent with Parliament, prolonging until resignation, ouster, death, or fresh election per subsection (2)(b), encapsulating the presidency's architectural continuity and foreseeable cadence, irrespective of the occupant's vicissitudes.

Conversely, section 91(2) links disqualification to antecedent "service" akin to "terms" - treating three or more years as a full term - implying "tenure" as the experiential habitation of the officeholder, possibly abbreviated by occurrences like removal, resignation or death. Thus, the "tenure" mentioned in section 97(1)(e) renders the removal criterion personal, based on the person's conduct amid their adaptable office-holding, not the inflexible institutional chronology. This lexical exactitude preserves the presidency as an abiding public fiduciary, detachable from any deficient occupant, assuring mid-tenure accountability without merging individual shortcomings with the office's eternal scaffold.

Section 95(2)(b) Enables Different Incumbents in One Term

Far from enforcing a personal threshold or term limit on any officeholder, section 95(2)(b) delineates the unitary institutional span of the 'Office of President' as five years, aligned with Parliament's vitality and tethered to electoral rhythms or constitutional eventualities such as ouster, resignation, or demise. Pivotal here is its stipulation that the term "continues until... the President-elect assumes office," mooring a fixed, communal timeframe to the office proper - not an assured allotment for the occupant. This architecture expressly permits plural successive officeholders within the identical five-year term without resetting the timeline, prioritising institutional endurance over individual prerogative.

This severance of the term's length from any singular incumbent's service manifests in succession protocols: Should a President resign, face removal under section 97, or perish after, say, two years, the successor - per section 101 - inherits solely the residual three years, continuing the extant term rather than initiating a fresh term. No starker exemplar exists than President Emmerson Mnangagwa's elevation on 24 November 2017: He fulfilled merely the concluding nine months of the five-year term commenced by his predecessor President Robert Mugabe in August 2013, culminating in August 2018 - not inaugurating a new five-year sequence.

Juxtapose this with authentic term-limit clauses, which affix constraints personally from the occupant's induction. For example, section 186(2) bounds Constitutional Court judges to a solitary, irrevocable 15-year term; section 205(2) confines Permanent Secretaries to up to five years, extendable once contingent on efficacy - anchored to the individual; whereas section 216(3) curbs Defence Forces Commanders to no exceeding five years per term, capped at two - again, individualised from inception.

These three examples illuminate a core dichotomy: section 95(2)(b) orchestrates the office's institutional temporal scope for administrative and public law imperatives, assuring fluid handovers, while genuine term-limits impose personal ceilings, mitigating extended dominion. Overlooking this distinction invites conflation of systemic protections with individual curbs, eroding the Constitution's meticulous design.

Section 95(2)(b) Has No Cumulative (10-Year) Term-Limit

Further buttressing the above, section 95(2)(b) - stipulating the President's term "continues until... the President-elect assumes office" - patently forgoes any term-limit function, restricting itself to outlining the malleable terminus of a single five-year term, modulated by exigencies like parliamentary dissolution, premature polls, removals, resignations or deaths without enforcing a cumulative lid on incumbency.

This absence is glaringly probative: whereas section 91(2) overtly caps presidential tenure at two terms (or a 10-year apex, reckoning three-plus years as plenary for disqualification), section 95(2)(b) is silent on such summation, abstaining from any quantitative or temporal barricade across manifold individual tenures within one five-year term of office. This intentional omission accentuates its delineative function - sculpting the institutional cadence of a term's expanse, not restraining an occupant's extended grasp - confirming the clause as a pure chronological template, unencumbered by term limits on the officeholder, to sustain democratic adaptability while distinct caps elsewhere impose anti-perpetuation accountability.

Term of Office of President in Zimbabwe Since 1980

The foregoing is neither revolutionary nor unprecedented but deeply entrenched in Zimbabwe's constitutional history. From 1980 to 2013 under the Lancaster House dispensation, "term of office" clauses operated exclusively as term-length provisions - defining the truncated institutional duration of the presidency - absent any numerical curb or ceiling on the incumbency of an occupant, echoing the core of section 95(2)(b) in the 2013 Constitution, which signifies historical continuity rather than rupture.

Initially, section 29(1) of the erstwhile Lancaster Constitution provided for a fixed six-year (ceremonial) presidential term, inaugurating upon oath and persisting until a successor's induction, with no bar to perpetual re-election; this emphasis on temporal scaffolding, without limits or caps, underscored the presidency as a perennial institution over a personal fiefdom bounded by term tallies.

Ensuing amendments upheld this definitional (time-span) essence: Constitution Amendment No. 7 (1987) - ushering the executive presidency - preserved the six-year interval while transitioning to a popular direct election by voters, still devoid of term limits or caps on the occupant, permitting then-President Robert Mugabe unbounded pursuits to remain in office indefinitely. By Amendment No. 18 (2007), section 29(1) evolved to a five-year term "concurrent with the life of Parliament," adaptable for dissolutions or prolongations under section 63, and concluding upon a new president's oath - mirroring precisely section 95(2)(b)'s coterminous tether to Parliament's lifespan, synchronising electoral cadence and governance without impeding re-eligibility.

This trajectory highlights the demarcation: Term-limit provisions (debuting only in 2013 under section 91(2) of the new Constitution, bounding at two terms) constrain personal tenure to avert power entrenchment, whereas term-length provisions akin to pre-2013 section 29 iterations under the former Lancaster Constitution and extant section 95(2)(b) merely sketch the office's rhythmic periodicity, nurturing institutional and administrative constancy and democratic rejuvenation without personal impediments, affirming section 95(2)(b) as an inherited, not contrived, apparatus in Zimbabwe's constitutional patrimony.

Amendment Implications: Duration Provisions Vs. Term-Limit Provisions

Section 95(2)(b) is amenable to amendment under section 328(5): As a duration or term-length clause about institutional rhythms, it adheres to the standard amendment protocol in section 328(5), demanding a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly and Senate, succeeded by presidential assent, without a national referendum. This efficient mechanism mirrors the operational character of the provision, affording leeway for functional tweaks while upholding electoral foreseeability.

This contrasts sharply with section 328(7), governing bona fide term-limit provisions. These curtail the tally of terms an officeholder may fulfil (e.g., section 91(2) for the President), mandating a ratifying national referendum under section 328(7) for any variation or abolition. This elevated barrier reflects their function in thwarting entrenched power, a worry extraneous to pure duration clauses that advance routine elections and institutional oversight.

The Mupungu Precedent

The foregoing aligns seamlessly with the Mupungu ratio decidendi. As determined by the Constitutional Court in Marx Mupungu v Minister of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs & 6 Ors (CCZ 7/21, 2021), a term-limit provision entails a fixed, ascertainable ceiling on the aggregate tenure of an officeholder (e.g., "two terms" or "renewable once"), accentuating personal ineligibility for re-election or re-appointment, over the mutable span of each term or institutional cycles.

The Mupungu precedent holds that a "term-limit provision" per section 328(1) curbs the "length of time" via rigid, capped intervals (e.g., non-extendable epochs), whereas "term of office" or "term length" denotes the duration or configuration of service, potentially variable. The age extension in section 186(3) evades term-limit status as it adjusts retirement predicated on aptitude, not immutable time. Accordingly, the Mupungu precedent sets a lucid boundary: Term-limit provisions enforce fixed, capped tenures on public officeholders, activating national referendum mandates for extensions under section 328(7), while term-length or term-of-office provisions outline adaptable durations without such caps, authorising amendments without national plebiscites.

In its interpretation of section 328(7) and term limits, the Constitutional Court held that: "A provision that prescribes an age limit for the holding or occupation of a particular office is not a 'term-limit provision' within the meaning of subsections (1) and (7) of section 328 of the Constitution. Any other interpretation would be contrary to the ordinary and grammatical meaning of the phrase 'term-limit'." Further: "Unlike age limits which may justify extension under exceptional circumstances, term limits under section 186(2) are absolute and do not allow for extensions beyond the prescribed number of terms."

The precise precept of the Mupungu precedent is that amendments to non-rigid, event-dependent tenure clauses (e.g., age limits) elude "term-limit" categorisation under section 328(7) and extend to incumbents unless explicitly barred. This logic bifurcates stringent term limits (delimited durations) from pliant age standards, with a wider schism between "term-limit provisions" and "term of office" or "term length" provisions, permitting extensions of flexible age criteria and variable term-of-office clauses without triggering a national referendum.

The ratio - that contingent, non-specific tenure provisions (alterable by occurrences like dissolution of Parliament or other contingencies such as removals, resignations or deaths) are not "term-limit provisions" under section 328(1) and (7) - bears profound ramifications for section 95(2)(b) (presidential term of office) and even 143(1) (parliamentary term of office), both nominating five years yet imbued with innate pliancy.

Since section 95(2)(b) stipulates that the presidential term of office "extends until" the ensuing election or other incidents (e.g., resignation, removal, deaths, constitutional overrides), is "coterminous with the life of Parliament," and endures "five years" except as otherwise stipulated; the Mupungu ratio implies that - like judicial age limits - this is provisional (intertwined with Parliament's fluctuating lifespan, e.g., premature dissolution under 143(2)), and is not a steadfast fixed term with predetermined termini. Hence, amending to extend from five to seven years would not constitute a "term-limit" amendment under 328(7), as it merely recalibrates a supple institutional timeframe (non-specific effluxion), not a bounded, fixed tenure epoch. Thus, it could pertain to incumbents without a national referendum (under 328(5)'s legislative route), circumventing 328(7)'s constraint, provided the extended term-length proves reasonable and justifiable in a constitutional democracy.

In the circumstances, the stipulation in section 328(7) that - "an amendment to a term-limit provision, the effect of which is to extend the length of time that a person may hold or occupy any public office, does not apply in relation to any person who held or occupied that office, or an equivalent office, at any time before the amendment" - bears no relevance whatsoever to section 95(2)(b), as the latter is not a "term-limit provision" at all. The stipulation applies solely to a "term-limit" provision like section 91(2).

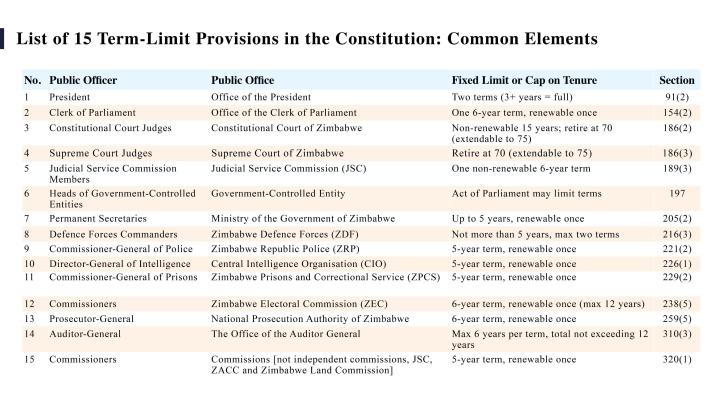

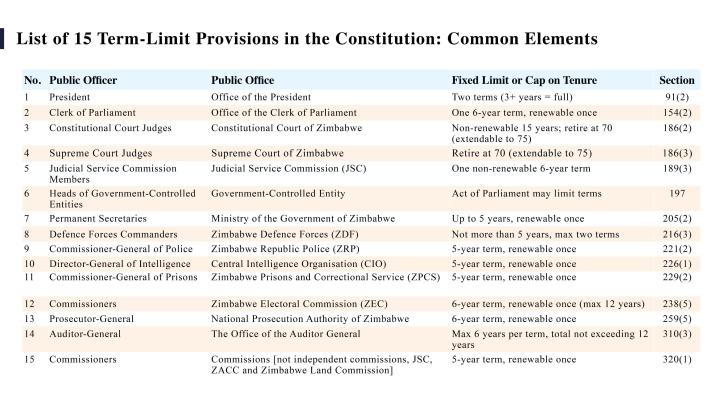

15 Term-Limit Provisions in the Constitution

The Constitution of Zimbabwe has an exhaustive number of 15 term-limit provisions, each overtly bounding or capping the personal tenure of public officers consistent with section 328(1)'s definition: "a provision of this Constitution which limits the length of time that a person may hold or occupy a public office." None of these 15 emulate - or is emulated by - section 95(2)(b) (a term-length provision on the President's term of office), which sketches an institutional duration without personal ceilings on the tenure of the officeholder. The table below crystallises this incontrovertibly: Any clause diverging from this archetype manifestly evades term-limit status under section 328(1).

Explanatory Note for Item 15 (Other Commissioners):

Explanatory Note for Item 15 (Other Commissioners):

Section 320(1) establishes a default term of five years, renewable for one additional term only, for members of Commissions unless the Constitution provides otherwise. However, section 320(2) specifies that members of Commissions - other than (a) the independent Commissions explicitly listed in section 232 (namely, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission, Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission, Zimbabwe Gender Commission, Zimbabwe Media Commission, and National Peace and Reconciliation Commission); (b) the Judicial Service Commission; (c) the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission; and (d) the Zimbabwe Land Commission - hold office at the pleasure of the President. This allows for discretionary removal at any time, without the procedural protections (e.g., for misconduct or incapacity via independent tribunals under sections like 237) that apply to the excluded commissions. Examples include members of the Public Service Commission (section 200), Police Service Commission (section 222), and similar bodies, where the term cap prevents indefinite service but offers no tenure security.

Parenthetically, and to dispel any ambiguity - considering the frequent and expedient misappropriation of Justice Patel's obiter inclusion of section 95(2) among exemplars he enumerates at pages 50/51 of the Mupungu judgment as "term-limit provisions" (encompassing sections 197, 216(3), 221(2), 226(1), and 229(2)) - it must be stressed that incorporating section 95(2) was a benign oversight. This is evident because section 95(2) shares no affinity with the other five sections cited by Justice Patel, which coalesce under a shared genus and indeed qualify as true term-limit provisions per subsections (1) and (7) of section 328. The apt presidential term-limit provision Justice Patel ought to have referenced in that obiter is section 91(2), not 95(2).

Beyond that, the three explicit and uniform characteristics or elements common to the 15 term-limit provisions in the above comprehensive catalogue from the Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013) - rendering them term-limit provisions - are as follows:

Element (i): Explicit Identification of the Affected Public Officer or Officeholder

This element specifies the particular occupant under capped or limited tenure, outlining the personal ambit and pertinence (e.g., "President," "judges of the Constitutional Court," "Permanent Secretary," or "Commanders of the Defence Forces").

Element (ii): Explicit Framing of the Temporal Initiation or Structure of the Tenure

This element utilises prefatory language to demarcate office occupation, establishing the basis for a bounded duration - such as "held office as…" (section 91(2), denoting prior or cumulative service); "appointed for…" (sections 154(2), 186(2) and (3), 189(3), 216(3), 221(2), 226(1), 229(2), 238(5), and 320(1), indicating entry into a confined period); "may limit the term…" (section 197, empowering a duration cap); "a period up to five years, and is renewable once only subject to competence, performance and delivery" (section 205(2), enforcing a conditional maximum); "a period of six years and is renewable for one further such term " (section 259(5), instituting a two-term ceiling); or "a period of not more than…" (section 310(3), imposing an upper limit) - thus forging the temporal scaffold for the ensuing constraint.

Element (iii): Explicit Imposition of a Numerical Cap on Terms or Cumulative Duration

This element applies a compulsory, quantifiable restraint on tenure, often with modifiers emphasising irrevocability, such as "non-renewable term," "renewable once only," "not more than two terms," or collective maxima (e.g., "up to a maximum of two terms" or "renewable once subject to competence and performance"), guaranteeing the tenure is finite, not open-ended.

Section 95(2)(b) lacks these three indispensable characteristics or elements of term-limit provisions and, for this cardinal reason, it is not a term-limit provision under subsections (1) and (7) of section 328.

This thorough enumeration and dissection irrefutably confirms that term-limit provisions in the Constitution of Zimbabwe are narrowly limited to personal tenure curbs or caps on public officers, enforcing fixed numerical restraints to avert indefinite incumbency and foster democratic turnover. The table and the essential triple elements furnish an impregnable classificatory structure, drawn from textual and judicial sources, illustrating that clauses like sections 95(2)(b) and 143(1) - which solely stipulate variable institutional durations or term lengths without personal disqualification - reside firmly beyond this category. Therefore, amendments varying such term lengths obviate referendum imperatives under section 328(7), empowering constitutional advancements to enhance governance resilience without procedural fetters, thereby upholding the Constitution's sanctity while propelling just, equitable and forward-looking constitutional reforms.

Term Limit and Term Length Provisions in a Global Perspective

This Zimbabwean schema harmonises with best international practice. Among all 193 United Nations member states, constitutional architectures invariably distinguish "term of office" provisions as institutional durations or term lengths - with fixed intervals like four to seven years for presidential mandates - assuring cyclical renewal of executive and legislative mandates without intrinsically capping the tenure or re-eligibility of incumbents, thus emphasising structural constancy over personal fetters.

This ubiquity arises from the elemental imperative for governance predictability: In presidential regimes (e.g., the four-year presidential term in the United States or Brazil's four-year term), the term length anchors electoral tempos; in parliamentary systems (e.g., the United Kingdom's maximum five-year parliamentary term, India's five-year Lok Sabha term); it indirectly circumscribes prime ministerial service via no-confidence votes or dissolutions, yet permits indefinite re-appointment if backing persists. Even in hybrid or authoritarian contexts (e.g., China's five-year presidential term, Russia's six-year term), term lengths endure as definitional anchors, frequently without numerical limits or caps.

Vitally, while all polities incorporate these durational clauses - validated in exhaustive overviews like World Population Review's compendium, spanning executives from Algeria to Zimbabwe - term limits (ceilings like two terms) are absent in roughly 50-60 nations, facilitating extended rule in countries such as Cameroon (unbounded seven-year presidential terms), Venezuela (unbounded six-year terms), Singapore (unbounded prime ministerial terms), and monarchies like Saudi Arabia (lifetime kingship with unbounded prime ministerial terms).This bifurcation accentuates term of office as an impartial institutional metronome, decoupled from the officeholder, cultivating democratic promise without compelling anti-consolidation bulwarks, which persist as elective and variably embraced to deter power accretion.

From a comparative lens, the instances of the United States, South Africa, and Botswana - featuring term-length provisions or institutional durations (presidential terms of office) discrete from presidential term-limit provisions - vividly exemplify the point.

The United States case delineates the schism between a term-limit provision and a term of office or term length, as evinced by Article II, Section 1, Clause 1 of the original U.S. Constitution (ratified 1788), which states:

"The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows…"

After 163 years, the 22nd Amendment (1951) appended a separate term-limit provision in Section 1:

"No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of the President more than once. But this article shall not apply to any person holding the office of President when this article was proposed by the Congress, and shall not prevent any person who may be holding the office of President, or acting as President, during the term within which this article becomes operative from holding the office of President or acting as President during the remainder of such term."

South Africa's presidential term length is articulated in section 88(1):

"The President's term of office begins on assuming office and ends upon a vacancy occurring or when the person next elected President assumes office."

A distinct term-limit provision resides in section 88(2):

"No person may hold office as President for more than two terms, but when a person is elected to fill a vacancy in the office of President, the period between that election and the next election of a President is not regarded as a term."

Botswana's presidential term length interlinks with Parliament's under section 91(3):

"Parliament, unless sooner dissolved, shall continue for five years from the date of the first sitting of the National Assembly after any dissolution and shall then stand dissolved."

A separate term-limit provision appears in section 34A:

"(1) A person shall not hold office as President for more than two terms, whether or not the terms are consecutive. (2) For the purposes of subsection (1), the service of a person as President for more than half of a term to which another person was elected shall be regarded as service for a term. (3) The provisions of this section shall not apply to a person holding office as President immediately before the coming into operation of this section."

Zimbabwe's section 95(2)(b) parallels Article II, Section 1, Clause 1 of the United States; section 88(1) of South Africa; and section 91(3) of Botswana - all institutional durations or single-term length provisions devoid of limits or caps on the tenure of incumbents - while Zimbabwe's section 91(2), the presidential term-limit provision, echoes Section 1 of the 22nd Amendment in the United States, section 88(2) in South Africa, and section 34A in Botswana - all term-limit provisions with limits or caps on incumbents.

Three Final Points Demonstrating That Section 95(2)(b) Is Not a Term-Limit Provision

As delineated thus far, the evidence is unassailable; it unequivocally confirms section 95(2)(b) as an institutional apparatus regulating the provisional and variable span of a presidential term of office, rather than a term-limit provision confining an incumbent's tenure. This vital demarcation is woven into the Constitution's fabric: While section 95(2)(b) outlines a term's culmination as persisting until resignation, removal, death, or the proclamation of a re-elected or new President - rendering it intrinsically adaptable and bound to electoral cadences and parliamentary vitalities - section 91(2) autonomously imposes personal disqualification post-two terms, wherein "three or more years' service" equates to a full term. Critically, this exegesis comports with section 328(1), which circumscribes a "term-limit provision" as one imposing a restraint on a public officer's tenure; section 95(2)(b) merely articulates or defines the functional length of a term for institutional perpetuity; it is not a bar on re-eligibility or service of an incumbent officeholder, thus it eludes the rigorous amendment shields under section 328(7), which guard against concurrent amendments to foundational constitutional protections governing the tenure of a designated public officeholder. The points below potently reinforce this verity, unmasking endeavours to equate "single term-length provisions" or durations of public offices with "term-limit provisions" on officeholders' tenure as profoundly erroneous and misguided.

(i) The Shared Term Between Mugabe and Mnangagwa Unequivocally Proves Institutional Duration or Term Length

The incontrovertible fact that Presidents Robert Mugabe and Emmerson Mnangagwa jointly consummated the 2013–2018 presidential term of office compellingly demonstrates that a "term of office of President" under section 95 constitutes an institutional armature pegged to the office's normative five-year cycle, coterminous with Parliament per section 95(1), rather than a personal prerogative or constraint on the incumbent. Mnangagwa's assumption of office on 24 November 2017, to finish Mugabe's incomplete term post his ouster did not spawn a fresh five-year term but fluidly sustained the existing one initiated in August 2013 after that year's harmonised general election, as the Constitution enables succession without recalibrating the institutional chronometer - per section 94(3), requiring the successor's oath within 48 hours of a vacancy. This mirrors section 95(2)(b)'s focus on a term's endpoint as dependent upon events like election proclamations, removals, or resignations; allowing plural incumbents within a solitary five-year cycle without violating the two-term personal cap in section 91(2).

Accordingly, Mnangagwa's qualification for his ensuing 2018 and 2023 terms legitimately omitted his fractional 2017–2018 nine-month interval from his personal cumulative term reckoning, deeming it the completion of an institutional term, not a plenary one under section 91(2). This seminal precedent decisively validates that section 95(2)(b) administers pragmatic duration to secure governance durability and efficacious public administration of the "Office of President," markedly segregated from curbs on individual officeholders - thereby dismantling any contention that the section operates as a term-limit provision or mechanism.

(ii) Mnangagwa's Possible 11-Year Cumulative Tenure Exposes the Contingent Nature of Variables Under Section 95(2)(b)

All factors constant, should President Mnangagwa persist in office until relinquishing at the end of his current term per section 95(2)(b), he would amass roughly 10 years and 9 to 10 months (practically 11 years) in a baseline scenario without a runoff. This estimation aggregates his service from his inaugural oath on 24 November 2017 (finalising Mugabe's 2013–2018 term), across his two complete five-year terms (2018–2023 and 2023–2028), to his successor's projected inauguration in early September 2028.

Historical patterns indicate Zimbabwe's general elections, with a few exceptions, typically occur in late July or August (e.g., 30 July 2018; 23-24 August 2023), with presidential induction 9–12 days post-results if unchallenged per section 94, or protracted amid disputes (as in 2018, deferred to 26 August). President Mnangagwa's 2023–2028 term lapses circa 4 September 2028, marking five years from his 4 September 2023, inauguration per section 95. Section 158 obliges polling no later than 30 days pre-expiry, situating it in early August to early September 2028. Positing a typical late-August election and early-September oath (e.g., 4 or 5 September, mirroring 2023), the exact duration tallies approximately 3,937 to 3,938 days - equating to about 10 years, 9 months, and 17–18 days, incorporating leap years in 2020, 2024, and 2028.

Nevertheless, this span might extend further - potentially surpassing 11 years - if the 2028 presidential race invokes a runoff under section 110(3)(i)(iii) of the Electoral Act, necessitating a runoff (absent a 50% + 1 vote majority), proclaimed by the President between 28 and 42 days post-original polling, with the Electoral Court authorised to extend the period for valid reasons upon being petitioned by the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC). For example, a late-August 2028 election could yield a runoff in late September (28 days) or mid-October (42 days), with results released within five days and prompt induction, deferring President Mnangagwa's handover to a successor to late September or mid-October 2028 - yielding circa 10 years and 10 months' cumulative term of office. With judicially sanctioned extensions (e.g., an extra 30 days for operational or legal causes), this might extend into November 2028 or later, culminating in 10 years and 11 months or more, and in outliers exceeding 11 full years if postponements cascade into 2029.

Fluctuations per the Electoral Act - like minimum 28-day proclamation notices, court-induced weeks-long delays, or runoff contingencies - could shift the successor's induction by two to four weeks or even beyond, maintaining the aggregate around 10 years and 9 months in routine instances, yet nearing or transcending 11 years with runoffs and extensions. Though section 95(2) posits a normative five-year term, coterminous with Parliament's lifespan per section 143(1), President Mnangagwa's possible protracted path from November 2017 to circa September 2028 or after; vividly evinces how actual service under section 95(2)(b) pivots on unforeseeable elements like ouster, resignation, election timing (section 158(1)), induction deferrals (section 94(1)), judicial intercessions, and runoff scenarios. This renders term-of-office durations under section 95(2)(b) as inherently variable or contingent as "age limits" under section 186. The Constitution eschews rigid endpoints in section 95, favouring event-contingent terms that endure until a successor's assumption of office per section 95(2)(b), accommodating real-world variances under the Electoral Act.

This innate pliancy nullifies the assumed 10-year apex (from two full five-year terms under section 95(2)(b)) as non-imperative, as attested by the 2018 petition's postponement or prospective 2028 analogues - including runoffs - that may protract handover into late 2028, early 2029, or further. Such irrefutable evidence cements section 95(2)(b) as a flexible duration or term length bulwark for institutional perseverance, not a stringent service cap or term-limit - contrasting acutely with the 15 authentic term-limit provisions elsewhere in the Constitution. Absent amendment to section 95(2)(b) as proposed, should President Mnangagwa's cumulative tenure approach or exceed 11 years owing to these contingencies, it would merely fortify the reality that section 95(2)(b) accommodates such extensions precisely because it is not a term-limit provision.

(iii) Alignment with Section 91(2)'s Adaptable Threshold Reinforces the Distinction

President Mnangagwa's aggregate service, as expounded, integrates flawlessly with section 91(2)'s term-limit framework, which bars service exceeding "two terms" but defines a "full term" as "three or more years' service" without mandating a maximum limit or cap per term. This minimum threshold intrinsically accommodates span variations from contingencies, paralleling section 95(2)(b)'s event-oriented closure (e.g., via election proclamation). Unlike unyielding boundaries (e.g., exactly five years), section 91(2) tolerates terms surpassing five years due to electoral lags, as illustrated in Mnangagwa's probable case - where his plenary terms (2018–2023 and 2023–2028) may surpass 10 years combined without disqualification, given his 2017 partial span falls below a full term. The overt "three or more years" clause in section 91(2) acknowledges such indeterminacies, affirming that section 95(2)(b) institutes variable institutional durations or term lengths, whereas section 91(2) tackles personal tenure pinnacles.

This consonance compellingly attests to section 95(2)(b)'s non-restrictive core, further illuminated by section 328(1)'s term-limit definition as impediments to officeholder tenure - standards that section 95(2)(b) fails to satisfy, as it facilitates rather than impedes protracted service through contingencies.

Conclusion

These interwoven contentions irrefutably render section 95(2)(b) a procedural, contingency-laden duration instrument or term length for the presidency's institutional edifice, wholly divergent from the incumbent-centric disqualifications in section 91(2). Attempts to conflate them - rampant in contemporary political rhetoric and grandstanding - emerge from tortured interpretations or political pursuits, yet the constitutional lexicon, judicial precedents, and delineations under section 328(1) and (7) resoundingly endorse this segregation, ensuring formidable defences against excess while conserving governance adaptability.

Under these auspices, the proposed amendment to section 95(2)(b) of the Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013) emerges as a transformative institutional linchpin. Though the initiative stemmed from ZANU-PF's National People's Conference - and while it understandably centred on the continuity of President Mnangagwa's leadership - the essence and purport of amending section 95(2)(b) transcend personal aggrandisement, representing an audacious institutional recalibration of the presidency's single-term duration from five to seven years. This reform, anchored in the "always speaking doctrine" applied by the Constitutional Court in the Mupungu case, would infuse perennial vitality into the nation's bedrock law, retroactively and prospectively reshaping the office of President, Parliaments, Local Authorities, and the service of all Presidents, MPs and Councillors - past, present, and future.

The "Always Speaking" Doctrine, enshrined in section 11 of Zimbabwe's Interpretation Act [Chapter 1:01] and invoked in Mupungu, constitutes a common-law interpretive tenet mandating dynamic construction of legislative clauses, applicable to emergent contexts and all pertinent persons or scenarios (past, present, and future) unless expressly precluded. Broadly, the doctrine assures the adaptability and equity of laws, averting absurdities like tenure voids while honouring their authentic intent.

In the ambit of the proposed amendments extending presidential and parliamentary terms of office from five to seven years under sections 95(2)(b) and 143(1), the doctrine proves instrumental: It rationalises continuity clauses enabling retroactive pertinence to incumbents elected at the 23-24 August 2023, harmonised general election, advancing impartial advantages across all impacted officeholders without favouritism.

The Constitutional Court deployed the "Always Speaking" Doctrine in Mupungu to "apply to the continuation in office of all judicial officers (mentioned in section 186 (1), (2) and (3)), including those judges who were incumbents of their respective offices before section 186 was amended," elucidating that non-obstante phrases (e.g., "notwithstanding section 328(7)") confirm non-encroachment on term-limit provisions - such as section 91(2) - permitting referendum-exempt amendments for non-capped durations or term lengths, like those in sections 95(2)(b) and 143(1). This pertinence safeguards against self-aggrandisement by any affected incumbent, guarantees seamless transitions, and underscores the constitutionality of the proposed amendments, cultivating stability by framing term-length amendments as institutional refinements rather than personal ceilings.

If enacted, these institutional overhauls would rectify structural deficiencies in abbreviated or shorter terms of office and direct presidential elections amid polarisation by addressing ground-level exigencies, buoyed not merely by Zanu-PF's 2024 Resolution Number 1 from Bulawayo - reaffirmed in 2025 at Mutare with an implementation timeline - but also by the 2019 appeal from the Zimbabwe Heads of Christian Denominations (ZHOCD) for a seven-year electoral hiatus to, among other aims, mend fissures largely spawned by the scourge of perennially disputed elections.

The profound impetus propelling this vista is not solely national but quintessentially Pan-African: The continent's arduously earned post-colonial insights reveal the hazards of curtailed four-to-five-year institutional cycles or term lengths, which stymie and derail development by ensnaring African states in perpetual, erosive electioneering - engendering disputed polls, societal cleavages, endemic corruption, and forsaken public welfare.

Conversely, a seven-year vista (analogous to Guinea's adoption in September 2025) would empower mitigation of "electoral fatigue" and surpass factional discords, redirecting vigour toward shared civic endeavours: resilient infrastructure development, the eradication of hunger and poverty, the vanquishing of disease, and the banishment of ignorance through education with a practical scientific purpose. This would transcend mere adjustment or tinkering; it would herald a visionary pivot toward stability, national unity, societal advancement, and cohesion, ensuring Zimbabwe's democracy flourishes not in ephemeral obscurity, but in the perpetual radiance of institutional fortitude to realise Vision 2030.

Dispelling Dangerous Myths

Yet, pernicious myths endure, clouding this clarity and imperilling essential reforms by distorting meaningful public discourse. Detractors mistakenly describe section 95(2)(b) as a sacrosanct "term-limit provision," adamantly claiming that its amendment is unattainable - or outright forbidden for sitting incumbents - without a referendum.

This fallacy of "unconstitutionality and illegality" is touted as an incontrovertible truth, with those who assert the myth brazenly declaring - devoid of any constitutional references, logical underpinnings, or judicial precedent - that such amendments are "unconstitutional and illegal" (as echoed by public intellectuals like Sipho Malunga: (https://x.com/SiphoMalunga/status/1991739985704390825?s=20). Regrettably, some prominent voices cloak their lack of evidence in abrasive, ad hominem tactics (for instance, Thabani Mpofu, who mobilises his ilk to vilify, caricature, and demonise proponents of amendment to section 95(2)(b) while sidestepping unavoidable courtroom challenges or meaningful public debate: https://x.com/adv_fulcrum/status/1982701171937521844?s=20); or through blatant misrepresentations in lieu of evidence-driven journalism (such as NewsHawks, whose editors have blatantly and falsely alleged this writer has argued that "there is a legal lacuna, a gap or loophole in the law' which can be used to ‘unconstitutionally and illegally" amend section 95(2)(b) - https://x.com/NewsHawksLive/status/1993890303728607247?s=20. This writer has not said anywhere or anytime that there's a lacuna in the law. Quite the contrary, this writer has been emphatically clear that sections 95(2(b) and 143(1) of the Constitution are not term limit provisions and that their amendment can be constitutionally and legally done under section 328(5) without requiring a national referendum.

Such personal attacks, distortions, and inventions are not only regrettable but utterly futile, serving only to muddy the waters of reasoned public discourse.

At its core, the constitutionality or legality of any amendment to the Constitution rests exclusively on adherence to the stipulated procedures - nothing else. From the inception of the presidential term of office extension proposal, the envisioned amendment to section 95(2)(b) complies fully with section 328, as interpreted alongside section 131; no deviations have been suggested or enacted by any party.

Compounding these myths is the pervasive "myth of authority," a common pitfall in constitutional debate where revered institutions (and certain influential individuals) leverage their presumed prestige to prop up baseless claims. This approach imparts an illusion of credibility to assertions bereft of objective proof, rigorous analysis, or precedential support. A poignant and dispiriting illustration comes from VeritasZim, widely esteemed as a supposedly neutral authority on Zimbabwean jurisprudence and legal matters. On 1 March 2024, VeritasZim published a thoughtful, balanced piece entitled "Extending the Presidential Term-Limit – Can it be Done?" (available at https://www.veritaszim.net/node/6888

). Therein, they posed a fundamental query: Which constitutional clauses would require amendment to extend the presidential term? Their unequivocal answer: "The first and most obvious amendment would be to section 91, which as we have seen sets out the current presidential term-limit."

Notably - and appropriately - VeritasZim omitted any reference to additional term-limit provisions beyond section 91(2). This exclusion was logical, as no properly-drafted democratic constitution redundantly replicates term-limit stipulations; such repetition would undermine the principles of precision and economy in legal drafting. However, fast-forward a year and a half to 9 November 2025, and VeritasZim released a remarkably parallel analysis, "Can the Presidential Term-Limit Be Extended?" (found at https://veritaszim.net/node/7732

). In a dramatic about-face, they declared that "sections 91(2) and 95(2) are both term-limit provisions," citing section 328(1)'s definition of a term-limit clause as "a provision of this Constitution which limits the length of time that a person may hold or occupy a public office."

This pronouncement wields the gravitas of expertise, yet it wilts under elementary examination - a bald assertion stripped of corroborating case law, intellectual insight, or even rudimentary interpretive logic. What prompted this sudden shift? In their 2024 analysis, section 95(2) was notably absent from term-limit deliberations, rendering this a tardy addendum. The timing itself invites scrutiny, hinting at extraneous political correctness beyond professional purity.

Exacerbating the inconsistency, VeritasZim's 2025 piece opens with a solid insight: "If it is decided to lengthen the presidential term from five to seven years, then section 95(1) of the Constitution would have to be amended, because it provides that the length of the President's term of office is: 'five years and coterminous with the life of Parliament.' The words 'five years' would need to be changed to 'seven years' and the words 'coterminous with the life of Parliament' would have to be deleted unless the life of Parliament is also to be extended to seven years."

This observation aptly positions section 95 as delineating the span of a solitary presidential term - five years, synchronised with Parliament's duration - as indicated by its explicit heading. It enforces no restriction on the quantity of terms, nor does it constrain the aggregate tenure of an officeholder. How, then, does it suddenly transmute into a term-limit provision? Solely through unsupported decree, mirroring the manoeuvres of political adversaries with whom VeritasZim now seems inadvertently or deliberately aligned at this pivotal moment, absent any substantive legal grounding.

A dispassionate juxtaposition of VeritasZim's March 2024 and November 2025 analyses yields an inescapable verdict: Section 95(2) does not constitute a term-limit provision per section 328(1), lacking any overt curb on presidential tenure. Claims otherwise stem not from fidelity to the constitutional text but from partisan mythologizing. In an age that demands unyielding legal probity, these last-minute somersaults undermine credibility and highlight the perils of unexamined authority. Zimbabweans merit better public discourse - meticulous information sharing over rhetorical legerdemain.

Institutional Nature of 'Office of President'

Within Zimbabwe's Constitution, section 95(2)(b) institutes a standardized, singular-duration structure of the presidency as a perpetual public institution, guaranteeing administrative seamlessness and electoral regularity every five years, rather than enforcing a tenure cap on specific occupants of the office. This qualifies it as a "duration or term-length provision," starkly differentiated from a "term-limit provision" that imposes a cumulative cap.

As a singular-duration clause, section 95(2)(b) mandates a consistent five-year rhythm for each electoral cycle, operating as a foundational descriptor of institutional process. It refrains from overseeing the aggregated service of individual occupants across successive terms, a matter handled distinctly (notably in section 91(2), which limits to two terms, with amendments invoking section 328(7)'s referendum safeguard).

Bearing the heading "Term of office of President and Vice-Presidents," section 95 specifies that the President's term endures until a successor's inauguration following an election, rooted in a five-year foundation (section 95(1)). It operationally binds the presidency's span to electoral results, enabling fluid transitions and alignment with parliamentary cycles under section 143. Functioning as a single-term directive, it facilitates the stewardship of public office through mandated recurrent elections, without impinging on personal re-election qualifications (regulated independently by section 91(2)).

The Electoral Act [Chapter 2:13], as amended, bolsters this institutional perspective in Part XVII, headed "Provisions Relating to Elections to the Office of President." Pertinent sections uniformly invoke "office of President" in headings and substance:

Section 104: "Nomination of candidates for election to office of President," outlining prerequisites for accessing the office.

Section 109: "Procedure after nomination day in election to office of President," detailing subsequent processes, including uncontested election declarations.

Section 110: "Election to office of President," regulating polling, tabulation, runoffs, and declarations, with the winner assuming office upon oath.

Section 111: "Election petitions in respect of election to office of President," enabling Constitutional Court contests to uphold the office's sanctity.

This consistent lexicon - stressing elections "to office of President," nominations for "office of President," and petitions concerning "office of President" - compels the inference that both the Constitution and Electoral Act envision the presidency as a "public office": a lasting public entity, separable from its temporary incumbent, promoting democratic perpetuity and oversight beyond mere personal incumbency.

Building on this institutional bedrock, the Constitution intentionally deploys "his or her tenure of office" in section 97(1)(e) - activating removal if the President acquires non-honorary foreign citizenship during that interval - to delineate "tenure" as the individualised, fluctuating extent of an incumbent's actual occupancy, distinct from the institutional, invariant "term of office of President."

Section 95(2) conceptualises "term of office" as a temporal yardstick: five years, concurrent with Parliament, prolonging until resignation, ouster, death, or fresh election per subsection (2)(b), encapsulating the presidency's architectural continuity and foreseeable cadence, irrespective of the occupant's vicissitudes.

Conversely, section 91(2) links disqualification to antecedent "service" akin to "terms" - treating three or more years as a full term - implying "tenure" as the experiential habitation of the officeholder, possibly abbreviated by occurrences like removal, resignation or death. Thus, the "tenure" mentioned in section 97(1)(e) renders the removal criterion personal, based on the person's conduct amid their adaptable office-holding, not the inflexible institutional chronology. This lexical exactitude preserves the presidency as an abiding public fiduciary, detachable from any deficient occupant, assuring mid-tenure accountability without merging individual shortcomings with the office's eternal scaffold.

Section 95(2)(b) Enables Different Incumbents in One Term

Far from enforcing a personal threshold or term limit on any officeholder, section 95(2)(b) delineates the unitary institutional span of the 'Office of President' as five years, aligned with Parliament's vitality and tethered to electoral rhythms or constitutional eventualities such as ouster, resignation, or demise. Pivotal here is its stipulation that the term "continues until... the President-elect assumes office," mooring a fixed, communal timeframe to the office proper - not an assured allotment for the occupant. This architecture expressly permits plural successive officeholders within the identical five-year term without resetting the timeline, prioritising institutional endurance over individual prerogative.

This severance of the term's length from any singular incumbent's service manifests in succession protocols: Should a President resign, face removal under section 97, or perish after, say, two years, the successor - per section 101 - inherits solely the residual three years, continuing the extant term rather than initiating a fresh term. No starker exemplar exists than President Emmerson Mnangagwa's elevation on 24 November 2017: He fulfilled merely the concluding nine months of the five-year term commenced by his predecessor President Robert Mugabe in August 2013, culminating in August 2018 - not inaugurating a new five-year sequence.

Juxtapose this with authentic term-limit clauses, which affix constraints personally from the occupant's induction. For example, section 186(2) bounds Constitutional Court judges to a solitary, irrevocable 15-year term; section 205(2) confines Permanent Secretaries to up to five years, extendable once contingent on efficacy - anchored to the individual; whereas section 216(3) curbs Defence Forces Commanders to no exceeding five years per term, capped at two - again, individualised from inception.

These three examples illuminate a core dichotomy: section 95(2)(b) orchestrates the office's institutional temporal scope for administrative and public law imperatives, assuring fluid handovers, while genuine term-limits impose personal ceilings, mitigating extended dominion. Overlooking this distinction invites conflation of systemic protections with individual curbs, eroding the Constitution's meticulous design.

Section 95(2)(b) Has No Cumulative (10-Year) Term-Limit

Further buttressing the above, section 95(2)(b) - stipulating the President's term "continues until... the President-elect assumes office" - patently forgoes any term-limit function, restricting itself to outlining the malleable terminus of a single five-year term, modulated by exigencies like parliamentary dissolution, premature polls, removals, resignations or deaths without enforcing a cumulative lid on incumbency.

This absence is glaringly probative: whereas section 91(2) overtly caps presidential tenure at two terms (or a 10-year apex, reckoning three-plus years as plenary for disqualification), section 95(2)(b) is silent on such summation, abstaining from any quantitative or temporal barricade across manifold individual tenures within one five-year term of office. This intentional omission accentuates its delineative function - sculpting the institutional cadence of a term's expanse, not restraining an occupant's extended grasp - confirming the clause as a pure chronological template, unencumbered by term limits on the officeholder, to sustain democratic adaptability while distinct caps elsewhere impose anti-perpetuation accountability.

Term of Office of President in Zimbabwe Since 1980

The foregoing is neither revolutionary nor unprecedented but deeply entrenched in Zimbabwe's constitutional history. From 1980 to 2013 under the Lancaster House dispensation, "term of office" clauses operated exclusively as term-length provisions - defining the truncated institutional duration of the presidency - absent any numerical curb or ceiling on the incumbency of an occupant, echoing the core of section 95(2)(b) in the 2013 Constitution, which signifies historical continuity rather than rupture.

Initially, section 29(1) of the erstwhile Lancaster Constitution provided for a fixed six-year (ceremonial) presidential term, inaugurating upon oath and persisting until a successor's induction, with no bar to perpetual re-election; this emphasis on temporal scaffolding, without limits or caps, underscored the presidency as a perennial institution over a personal fiefdom bounded by term tallies.

Ensuing amendments upheld this definitional (time-span) essence: Constitution Amendment No. 7 (1987) - ushering the executive presidency - preserved the six-year interval while transitioning to a popular direct election by voters, still devoid of term limits or caps on the occupant, permitting then-President Robert Mugabe unbounded pursuits to remain in office indefinitely. By Amendment No. 18 (2007), section 29(1) evolved to a five-year term "concurrent with the life of Parliament," adaptable for dissolutions or prolongations under section 63, and concluding upon a new president's oath - mirroring precisely section 95(2)(b)'s coterminous tether to Parliament's lifespan, synchronising electoral cadence and governance without impeding re-eligibility.

This trajectory highlights the demarcation: Term-limit provisions (debuting only in 2013 under section 91(2) of the new Constitution, bounding at two terms) constrain personal tenure to avert power entrenchment, whereas term-length provisions akin to pre-2013 section 29 iterations under the former Lancaster Constitution and extant section 95(2)(b) merely sketch the office's rhythmic periodicity, nurturing institutional and administrative constancy and democratic rejuvenation without personal impediments, affirming section 95(2)(b) as an inherited, not contrived, apparatus in Zimbabwe's constitutional patrimony.

Amendment Implications: Duration Provisions Vs. Term-Limit Provisions

Section 95(2)(b) is amenable to amendment under section 328(5): As a duration or term-length clause about institutional rhythms, it adheres to the standard amendment protocol in section 328(5), demanding a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly and Senate, succeeded by presidential assent, without a national referendum. This efficient mechanism mirrors the operational character of the provision, affording leeway for functional tweaks while upholding electoral foreseeability.

This contrasts sharply with section 328(7), governing bona fide term-limit provisions. These curtail the tally of terms an officeholder may fulfil (e.g., section 91(2) for the President), mandating a ratifying national referendum under section 328(7) for any variation or abolition. This elevated barrier reflects their function in thwarting entrenched power, a worry extraneous to pure duration clauses that advance routine elections and institutional oversight.

The Mupungu Precedent

The foregoing aligns seamlessly with the Mupungu ratio decidendi. As determined by the Constitutional Court in Marx Mupungu v Minister of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs & 6 Ors (CCZ 7/21, 2021), a term-limit provision entails a fixed, ascertainable ceiling on the aggregate tenure of an officeholder (e.g., "two terms" or "renewable once"), accentuating personal ineligibility for re-election or re-appointment, over the mutable span of each term or institutional cycles.

The Mupungu precedent holds that a "term-limit provision" per section 328(1) curbs the "length of time" via rigid, capped intervals (e.g., non-extendable epochs), whereas "term of office" or "term length" denotes the duration or configuration of service, potentially variable. The age extension in section 186(3) evades term-limit status as it adjusts retirement predicated on aptitude, not immutable time. Accordingly, the Mupungu precedent sets a lucid boundary: Term-limit provisions enforce fixed, capped tenures on public officeholders, activating national referendum mandates for extensions under section 328(7), while term-length or term-of-office provisions outline adaptable durations without such caps, authorising amendments without national plebiscites.

In its interpretation of section 328(7) and term limits, the Constitutional Court held that: "A provision that prescribes an age limit for the holding or occupation of a particular office is not a 'term-limit provision' within the meaning of subsections (1) and (7) of section 328 of the Constitution. Any other interpretation would be contrary to the ordinary and grammatical meaning of the phrase 'term-limit'." Further: "Unlike age limits which may justify extension under exceptional circumstances, term limits under section 186(2) are absolute and do not allow for extensions beyond the prescribed number of terms."

The precise precept of the Mupungu precedent is that amendments to non-rigid, event-dependent tenure clauses (e.g., age limits) elude "term-limit" categorisation under section 328(7) and extend to incumbents unless explicitly barred. This logic bifurcates stringent term limits (delimited durations) from pliant age standards, with a wider schism between "term-limit provisions" and "term of office" or "term length" provisions, permitting extensions of flexible age criteria and variable term-of-office clauses without triggering a national referendum.

The ratio - that contingent, non-specific tenure provisions (alterable by occurrences like dissolution of Parliament or other contingencies such as removals, resignations or deaths) are not "term-limit provisions" under section 328(1) and (7) - bears profound ramifications for section 95(2)(b) (presidential term of office) and even 143(1) (parliamentary term of office), both nominating five years yet imbued with innate pliancy.

Since section 95(2)(b) stipulates that the presidential term of office "extends until" the ensuing election or other incidents (e.g., resignation, removal, deaths, constitutional overrides), is "coterminous with the life of Parliament," and endures "five years" except as otherwise stipulated; the Mupungu ratio implies that - like judicial age limits - this is provisional (intertwined with Parliament's fluctuating lifespan, e.g., premature dissolution under 143(2)), and is not a steadfast fixed term with predetermined termini. Hence, amending to extend from five to seven years would not constitute a "term-limit" amendment under 328(7), as it merely recalibrates a supple institutional timeframe (non-specific effluxion), not a bounded, fixed tenure epoch. Thus, it could pertain to incumbents without a national referendum (under 328(5)'s legislative route), circumventing 328(7)'s constraint, provided the extended term-length proves reasonable and justifiable in a constitutional democracy.

In the circumstances, the stipulation in section 328(7) that - "an amendment to a term-limit provision, the effect of which is to extend the length of time that a person may hold or occupy any public office, does not apply in relation to any person who held or occupied that office, or an equivalent office, at any time before the amendment" - bears no relevance whatsoever to section 95(2)(b), as the latter is not a "term-limit provision" at all. The stipulation applies solely to a "term-limit" provision like section 91(2).

15 Term-Limit Provisions in the Constitution

The Constitution of Zimbabwe has an exhaustive number of 15 term-limit provisions, each overtly bounding or capping the personal tenure of public officers consistent with section 328(1)'s definition: "a provision of this Constitution which limits the length of time that a person may hold or occupy a public office." None of these 15 emulate - or is emulated by - section 95(2)(b) (a term-length provision on the President's term of office), which sketches an institutional duration without personal ceilings on the tenure of the officeholder. The table below crystallises this incontrovertibly: Any clause diverging from this archetype manifestly evades term-limit status under section 328(1).

Explanatory Note for Item 15 (Other Commissioners):

Explanatory Note for Item 15 (Other Commissioners):Section 320(1) establishes a default term of five years, renewable for one additional term only, for members of Commissions unless the Constitution provides otherwise. However, section 320(2) specifies that members of Commissions - other than (a) the independent Commissions explicitly listed in section 232 (namely, the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission, Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission, Zimbabwe Gender Commission, Zimbabwe Media Commission, and National Peace and Reconciliation Commission); (b) the Judicial Service Commission; (c) the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission; and (d) the Zimbabwe Land Commission - hold office at the pleasure of the President. This allows for discretionary removal at any time, without the procedural protections (e.g., for misconduct or incapacity via independent tribunals under sections like 237) that apply to the excluded commissions. Examples include members of the Public Service Commission (section 200), Police Service Commission (section 222), and similar bodies, where the term cap prevents indefinite service but offers no tenure security.

Parenthetically, and to dispel any ambiguity - considering the frequent and expedient misappropriation of Justice Patel's obiter inclusion of section 95(2) among exemplars he enumerates at pages 50/51 of the Mupungu judgment as "term-limit provisions" (encompassing sections 197, 216(3), 221(2), 226(1), and 229(2)) - it must be stressed that incorporating section 95(2) was a benign oversight. This is evident because section 95(2) shares no affinity with the other five sections cited by Justice Patel, which coalesce under a shared genus and indeed qualify as true term-limit provisions per subsections (1) and (7) of section 328. The apt presidential term-limit provision Justice Patel ought to have referenced in that obiter is section 91(2), not 95(2).

Beyond that, the three explicit and uniform characteristics or elements common to the 15 term-limit provisions in the above comprehensive catalogue from the Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013) - rendering them term-limit provisions - are as follows:

Element (i): Explicit Identification of the Affected Public Officer or Officeholder

This element specifies the particular occupant under capped or limited tenure, outlining the personal ambit and pertinence (e.g., "President," "judges of the Constitutional Court," "Permanent Secretary," or "Commanders of the Defence Forces").

Element (ii): Explicit Framing of the Temporal Initiation or Structure of the Tenure

This element utilises prefatory language to demarcate office occupation, establishing the basis for a bounded duration - such as "held office as…" (section 91(2), denoting prior or cumulative service); "appointed for…" (sections 154(2), 186(2) and (3), 189(3), 216(3), 221(2), 226(1), 229(2), 238(5), and 320(1), indicating entry into a confined period); "may limit the term…" (section 197, empowering a duration cap); "a period up to five years, and is renewable once only subject to competence, performance and delivery" (section 205(2), enforcing a conditional maximum); "a period of six years and is renewable for one further such term " (section 259(5), instituting a two-term ceiling); or "a period of not more than…" (section 310(3), imposing an upper limit) - thus forging the temporal scaffold for the ensuing constraint.

Element (iii): Explicit Imposition of a Numerical Cap on Terms or Cumulative Duration

This element applies a compulsory, quantifiable restraint on tenure, often with modifiers emphasising irrevocability, such as "non-renewable term," "renewable once only," "not more than two terms," or collective maxima (e.g., "up to a maximum of two terms" or "renewable once subject to competence and performance"), guaranteeing the tenure is finite, not open-ended.

Section 95(2)(b) lacks these three indispensable characteristics or elements of term-limit provisions and, for this cardinal reason, it is not a term-limit provision under subsections (1) and (7) of section 328.

This thorough enumeration and dissection irrefutably confirms that term-limit provisions in the Constitution of Zimbabwe are narrowly limited to personal tenure curbs or caps on public officers, enforcing fixed numerical restraints to avert indefinite incumbency and foster democratic turnover. The table and the essential triple elements furnish an impregnable classificatory structure, drawn from textual and judicial sources, illustrating that clauses like sections 95(2)(b) and 143(1) - which solely stipulate variable institutional durations or term lengths without personal disqualification - reside firmly beyond this category. Therefore, amendments varying such term lengths obviate referendum imperatives under section 328(7), empowering constitutional advancements to enhance governance resilience without procedural fetters, thereby upholding the Constitution's sanctity while propelling just, equitable and forward-looking constitutional reforms.

Term Limit and Term Length Provisions in a Global Perspective

This Zimbabwean schema harmonises with best international practice. Among all 193 United Nations member states, constitutional architectures invariably distinguish "term of office" provisions as institutional durations or term lengths - with fixed intervals like four to seven years for presidential mandates - assuring cyclical renewal of executive and legislative mandates without intrinsically capping the tenure or re-eligibility of incumbents, thus emphasising structural constancy over personal fetters.

This ubiquity arises from the elemental imperative for governance predictability: In presidential regimes (e.g., the four-year presidential term in the United States or Brazil's four-year term), the term length anchors electoral tempos; in parliamentary systems (e.g., the United Kingdom's maximum five-year parliamentary term, India's five-year Lok Sabha term); it indirectly circumscribes prime ministerial service via no-confidence votes or dissolutions, yet permits indefinite re-appointment if backing persists. Even in hybrid or authoritarian contexts (e.g., China's five-year presidential term, Russia's six-year term), term lengths endure as definitional anchors, frequently without numerical limits or caps.

Vitally, while all polities incorporate these durational clauses - validated in exhaustive overviews like World Population Review's compendium, spanning executives from Algeria to Zimbabwe - term limits (ceilings like two terms) are absent in roughly 50-60 nations, facilitating extended rule in countries such as Cameroon (unbounded seven-year presidential terms), Venezuela (unbounded six-year terms), Singapore (unbounded prime ministerial terms), and monarchies like Saudi Arabia (lifetime kingship with unbounded prime ministerial terms).This bifurcation accentuates term of office as an impartial institutional metronome, decoupled from the officeholder, cultivating democratic promise without compelling anti-consolidation bulwarks, which persist as elective and variably embraced to deter power accretion.