News / National

When Mutare sleeps, the night economy wakes

24 Jan 2026 at 08:36hrs |

0 Views

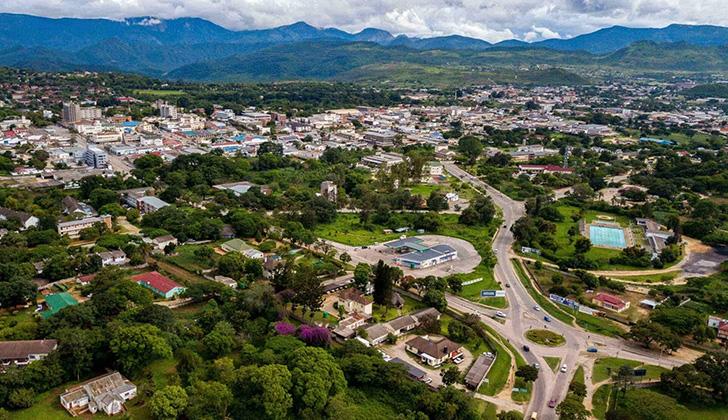

When the sun sinks behind Mutare's green hills, the city quietly changes its rhythm. High-density suburbs such as Sakubva, Chikanga, Dangamvura, Hobhouse, Zimta and Gimboki, together with the Central Business District, take on a different kind of energy as vendors pack up, commuter omnibuses thin out after 9pm, and the night economy cautiously steps forward.

For the city's sex workers, nightfall signals the start of the working day.

For Mary (not her real name), preparations begin long before she meets her first client. With unreliable water and electricity, a cold bath replaces a warm one, makeup is applied in a cracked mirror, and her phone is charged at a neighbour's house. By the time bars in the suburbs fill up and clubs in the city centre come alive, she is already calculating prices, risks and survival.

In Chikanga and Dangamvura, beerhalls and street corners become informal marketplaces. Under dim lights, women line up along walls and fences, their clothing as much a uniform as it is a shield. A "short time" can cost as little as US$3 — quick, rushed and often risky. Low prices, the women say, attract desperation on both sides, sometimes leading to violence, disputes and police raids that scatter everyone into the darkness.

Health concerns loom over every interaction. Condoms are the norm, but poverty complicates decisions. Some clients offer more money for unsafe encounters, a reality the women describe as a cruel bargaining system where hunger competes with fear of illness.

"HIV here is not a statistic," Mary said in an interview. "It has faces and names. I lost my best friend in 2019. One decision changed her life."

She says she tests regularly and carries her own protection, but risk remains constant, especially when alcohol is involved. "The worst nights are when anger mixes with drink. We run, we lose money, sometimes even shoes. But there are also nights when a client treats you like a human being. Those moments remind me that I still matter."

As the night deepens, activity shifts towards clubs closer to the city centre, where music blares and security guards provide a thin layer of protection. Prices rise, but so do expectations.

Tariro (26), from Dangamvura, says she prefers working in city clubs because the pay is better, even though the risks are different. Orphaned at a young age, she came to Mutare in search of work but found few opportunities.

"In clubs, the money can be US$10 or more, but some men think paying more means owning you," she said. "They make demands and threaten you when you refuse. Hunger pushes people into decisions they don't want to make."

By around 3am, exhaustion sets in. Heels hurt, voices grow hoarse, and those still standing lean on one another, sharing cigarettes, warnings and quiet laughter.

Mai Chipo (41), popularly known as Rasta, is a veteran of the streets and well-known across several towns. Living with HIV, she says survival depends on discipline and solidarity.

"I teach the young ones rules — never go alone, never leave your drink, never trust someone who refuses protection," she said. "Life didn't end when I found out my status. It changed. What hurts is the stigma. People want us at night and judge us by day."

As dawn approaches, the women melt back into the city's morning crowds, returning to their homes while the night's stories fade with the darkness.

The interviews were not easy to secure. Many were initially reluctant to speak, but their accounts reflect the harsh realities of survival in an economy driven by poverty and limited opportunity.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in sex workers frequenting parts of Mutare's city centre, including one of its oldest brothels. Some attribute the surge to stories of sudden wealth, including a widely circulated 2021 incident in which a sex worker reportedly received a large payment from a single client.

Whether myth or motivation, such stories continue to fuel hope in the shadows of the city — hope that one good night might change everything.

For the city's sex workers, nightfall signals the start of the working day.

For Mary (not her real name), preparations begin long before she meets her first client. With unreliable water and electricity, a cold bath replaces a warm one, makeup is applied in a cracked mirror, and her phone is charged at a neighbour's house. By the time bars in the suburbs fill up and clubs in the city centre come alive, she is already calculating prices, risks and survival.

In Chikanga and Dangamvura, beerhalls and street corners become informal marketplaces. Under dim lights, women line up along walls and fences, their clothing as much a uniform as it is a shield. A "short time" can cost as little as US$3 — quick, rushed and often risky. Low prices, the women say, attract desperation on both sides, sometimes leading to violence, disputes and police raids that scatter everyone into the darkness.

Health concerns loom over every interaction. Condoms are the norm, but poverty complicates decisions. Some clients offer more money for unsafe encounters, a reality the women describe as a cruel bargaining system where hunger competes with fear of illness.

"HIV here is not a statistic," Mary said in an interview. "It has faces and names. I lost my best friend in 2019. One decision changed her life."

She says she tests regularly and carries her own protection, but risk remains constant, especially when alcohol is involved. "The worst nights are when anger mixes with drink. We run, we lose money, sometimes even shoes. But there are also nights when a client treats you like a human being. Those moments remind me that I still matter."

As the night deepens, activity shifts towards clubs closer to the city centre, where music blares and security guards provide a thin layer of protection. Prices rise, but so do expectations.

Tariro (26), from Dangamvura, says she prefers working in city clubs because the pay is better, even though the risks are different. Orphaned at a young age, she came to Mutare in search of work but found few opportunities.

"In clubs, the money can be US$10 or more, but some men think paying more means owning you," she said. "They make demands and threaten you when you refuse. Hunger pushes people into decisions they don't want to make."

By around 3am, exhaustion sets in. Heels hurt, voices grow hoarse, and those still standing lean on one another, sharing cigarettes, warnings and quiet laughter.

Mai Chipo (41), popularly known as Rasta, is a veteran of the streets and well-known across several towns. Living with HIV, she says survival depends on discipline and solidarity.

"I teach the young ones rules — never go alone, never leave your drink, never trust someone who refuses protection," she said. "Life didn't end when I found out my status. It changed. What hurts is the stigma. People want us at night and judge us by day."

As dawn approaches, the women melt back into the city's morning crowds, returning to their homes while the night's stories fade with the darkness.

The interviews were not easy to secure. Many were initially reluctant to speak, but their accounts reflect the harsh realities of survival in an economy driven by poverty and limited opportunity.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in sex workers frequenting parts of Mutare's city centre, including one of its oldest brothels. Some attribute the surge to stories of sudden wealth, including a widely circulated 2021 incident in which a sex worker reportedly received a large payment from a single client.

Whether myth or motivation, such stories continue to fuel hope in the shadows of the city — hope that one good night might change everything.

Source - Manica Post

Join the discussion

Loading comments…