News / National

Ex-CIO boss's father was killed after being branded a sellout

20 Oct 2024 at 13:47hrs |

0 Views

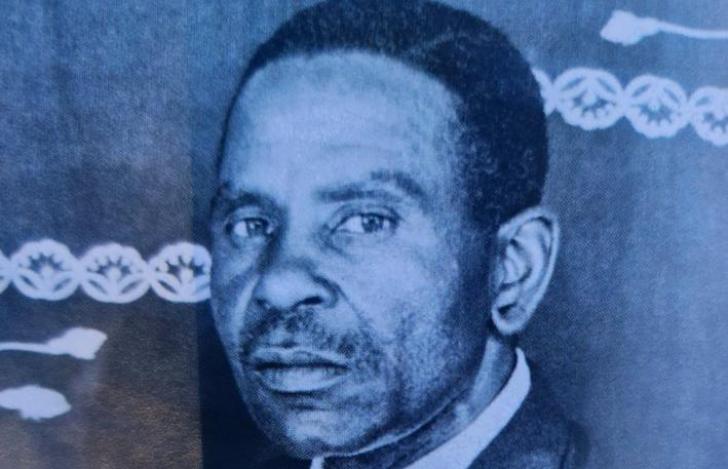

Former Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) Director-General Happyton Bonyongwe has opened up about the devastating impact of the liberation struggle on his family, recounting the tragic murder of his father at the hands of "comrades" during the late 1970s. Bonyongwe's father, Elisha Khumbuyani Bonyongwe, was accused of being a "sellout" by enemies in their Honde Valley village, leading to his untimely death.

Elisha Bonyongwe, originally from Chipinge in Manicaland, had settled in Honde Valley. On November 30, 1977, he was killed at Govingo Business Centre, a location accessible via a road running from Watsomba Business Centre on the Mutare-Nyanga road.

Reflecting on his father's plight, Bonyongwe stated, “When I left in 1975, I am told my father was distraught despite giving me his blessing. In Shona tradition, his one and only heir had left for a war, putting his life in jeopardy.†He noted that his father sought solace through the church, even building a place of worship at Muparutsa.

As the conflict intensified, Bonyongwe's family faced significant challenges. Following the establishment of "keeps" or protected villages in the area, they relocated to Govingo Shopping Centre, where Elisha rented a shop and constructed a home for his family, including Bonyongwe's mother, Celia Mbavhumana, and his sister Gladys.

However, turmoil struck the family when Elisha took a second wife from Inyanga, resulting in the birth of a son named Thompson. Bonyongwe described the relationship between his father and his new wife as tumultuous, stating, “Thompson's mother, Mai Thompson, also wanted my father's wealth for herself, or so the story went.â€

Bonyongwe detailed how jealousy and conflict ensued, ultimately leading to Mai Thompson working with a war collaborator to falsely accuse Elisha of being a sellout. On the fateful night of November 30, 1977, comrades mistakenly included Elisha in a group of individuals targeted for execution. Tragically, he was killed alongside a retired policeman and a man suspected of being a member of the Selous Scouts.

“This was a tragic ending to a good and illustrious life,†Bonyongwe lamented. He highlighted the irony of his father's support for the liberation cause, having sent his only son to join the fight.

Following the murders, the bodies of the alleged "sell-outs" were left unburied. On December 1, 1977, the Rhodesians collected the bodies of two known collaborators but left Elisha’s corpse exposed at the site of his death. “My mother and some villagers appealed to the kraalhead to intervene,†Bonyongwe recounted.

Eventually, with the help of comrades familiar with Elisha’s genuine support for the liberation efforts, his body was allowed to be buried in the village cemetery at Govingo.

This harrowing account underscores the complexities and tragedies faced by families during Zimbabwe's liberation struggle, highlighting the deep scars that remain long after the conflict has ended.

Elisha Bonyongwe, originally from Chipinge in Manicaland, had settled in Honde Valley. On November 30, 1977, he was killed at Govingo Business Centre, a location accessible via a road running from Watsomba Business Centre on the Mutare-Nyanga road.

Reflecting on his father's plight, Bonyongwe stated, “When I left in 1975, I am told my father was distraught despite giving me his blessing. In Shona tradition, his one and only heir had left for a war, putting his life in jeopardy.†He noted that his father sought solace through the church, even building a place of worship at Muparutsa.

As the conflict intensified, Bonyongwe's family faced significant challenges. Following the establishment of "keeps" or protected villages in the area, they relocated to Govingo Shopping Centre, where Elisha rented a shop and constructed a home for his family, including Bonyongwe's mother, Celia Mbavhumana, and his sister Gladys.

However, turmoil struck the family when Elisha took a second wife from Inyanga, resulting in the birth of a son named Thompson. Bonyongwe described the relationship between his father and his new wife as tumultuous, stating, “Thompson's mother, Mai Thompson, also wanted my father's wealth for herself, or so the story went.â€

Bonyongwe detailed how jealousy and conflict ensued, ultimately leading to Mai Thompson working with a war collaborator to falsely accuse Elisha of being a sellout. On the fateful night of November 30, 1977, comrades mistakenly included Elisha in a group of individuals targeted for execution. Tragically, he was killed alongside a retired policeman and a man suspected of being a member of the Selous Scouts.

“This was a tragic ending to a good and illustrious life,†Bonyongwe lamented. He highlighted the irony of his father's support for the liberation cause, having sent his only son to join the fight.

Following the murders, the bodies of the alleged "sell-outs" were left unburied. On December 1, 1977, the Rhodesians collected the bodies of two known collaborators but left Elisha’s corpse exposed at the site of his death. “My mother and some villagers appealed to the kraalhead to intervene,†Bonyongwe recounted.

Eventually, with the help of comrades familiar with Elisha’s genuine support for the liberation efforts, his body was allowed to be buried in the village cemetery at Govingo.

This harrowing account underscores the complexities and tragedies faced by families during Zimbabwe's liberation struggle, highlighting the deep scars that remain long after the conflict has ended.

Source - online

Join the discussion

Loading comments…